|

[ Outlaw Genealogy | Bruce

History | Lost Chords ] [ Projects | News | FAQ | Suggestions | Search | HotLinks | Resources | Ufo ] |

|

[ Outlaw Genealogy | Bruce

History | Lost Chords ] [ Projects | News | FAQ | Suggestions | Search | HotLinks | Resources | Ufo ] |

I am looking at another angle I had not thought of before, The colonization of Iceland by the Vikings around 900 AD , Harald The FairHair (Norway) began his "unification" of the country creating many "Exiles" and "Outlaws" who left in their ships for safer places to live. So this maybe the proto origin of the "Utlagi" family. Iceland has it's own "outlaw" sagas that although were written in the Twelfth-13th century were written about the 10th.

700~1000AD - Útlagi

placed this stone in memory of Sveinn -Rune sm103 - Småland,

Sweden

990~1010AD - Utlage

raised this stone in memory of Öjvind, a very good thegn -

Rune vg62 - Ballstorp, Västergötland, Sweden

957 - Outlawe(s) Banished

for political offences to Ireland by King Edwy - St. Dunstan Banished

959 - Outlawe(s) Return to England "with many wolves

heads" under King

Edgar reigns - St. Dunstan returns - 1613

Visitation Legend

960 - King

Edgar general pardon in return for a certain number of wolves' tongues

from each criminal

See for reference: Outlawe - The Wuffings - St. Edmund - King Edwy

During the years 800-1200, Iceland and Greenland were settled by the Vikings. These people, also known as the Norse, included Norwegians, Swedes, Danes, and Finns

The Norse peoples traveled to Iceland for a variety of reasons including a search for more land and resources to satisfy a growing population and to escape raiders and harsh rulers. One force behind the movement to Iceland in the ninth century was the ruthlessness of Harald Fairhair, a Norwegian King (Bryson, 1977.)

Greenland

Vikings

Greenland

Vikings

In 960, Thorvald Asvaldsson of Jaederen in Norway killed a man. He was forced to leave the country so he moved to northern Iceland. He had a ten year old son named Eric, later to be called Eric Röde, or Eric the Red. Eric too had a violent streak and in 982 he killed two men. Eric the Red was banished from Iceland for three years so he sailed west to find a land that Icelanders had discovered years before but knew little about. Eric searched the coast of this land and found the most hospitable area, a deep fiord on the southwestern coast. Warmer Atlantic currents met the island there and conditions were not much different than those in Iceland (trees and grasses.) He called this new land "Greenland" because he "believed more people would go thither if the country had a beautiful name," according to one of the Icelandic chronicles (Hermann, 1954) although Greenland, as a whole, could not be considered "green." Additionally, the land was not very good for farming. Nevertheless, Eric was able to draw thousands to the three areas shown in Fig. 15.

Three Outlaw Sagas - Three Icelandic Outlaw Sagas. The Saga of Gisli. The Saga of Grettir. The Saga of Hord. Translated by G. Johnston and A. Faulkes. Edited and Introduced by A. Faulkes.

The three sagas translated from Old Icelandic in this volume are all about Icelanders in the Middle Ages who lived and died as outlaws in the Icelandic

countryside. Like all other sagas of Icelanders, these three are anonymous, but

they were certainly written by Icelanders, probably in the west or north-west of

Iceland. It is likely that The Saga of Gisli was written in the first half of the thirteenth century, perhaps about 1230, and thus is part of the first flowering of 'classical' Icelandic sagas. The Saga of Grettir is quite a lot later, from the fourteenth century, probably from about 1320 and later than most other sagas of Icelanders. Indeed the most recent editor of the saga (Örnólfur Thorsson, 1994) suggests that it may be from as late as the end of the fourteenth century. The Saga of Hord (called Holmveria saga, 'the Saga of the Holm-dwellers', in the principal manuscript) is also a late saga, probably from the second half of the fourteenth century. These last two sagas were therefore written quite a long time after the Icelandic Commonwealth was ceded to the Norwegian Crown in 1262-3, possibly even as late as the time of the union of the Norwegian, Swedish and Danish crowns (1397); and also after translated Romances and Heroic Sagas (fornaldar sögur, Sagas of Ancient Time or Legendary Sagas) may be regarded as having to a large extent superseded Sagas of Icelanders as the primary expression of Icelandic identity and values.

The attitudes to outlawry in Iceland in these texts are interesting to compare with those in English outlaw traditions; the earliest surviving legends of Robin Hood are from the fifteenth century.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=76AlJZuywXo

Útlaginn

(Outlaw: The Saga of Gisli) is an Icelandic

movie

filmed in 1981, detailing a blood

feud that took place in Viking

times. It is based upon one of the Icelanders'

Sagas called the Gísla

saga.

Útlaginn

(Outlaw: The Saga of Gisli) is an Icelandic

movie

filmed in 1981, detailing a blood

feud that took place in Viking

times. It is based upon one of the Icelanders'

Sagas called the Gísla

saga.

The film was released on 17 February 1984 to critical acclaim in Sweden,

and then in West

Germany. Written and directed by Ágúst

Guðmundsson, the theatrical version of the Saga of Gisli Sursson is said to

be an extremely culturally accurate representation of the peoples of the time

period.

...

This movie follows the story of Gisli, his family, and his adventures as an

outlaw included in the thirteenth century Icelandic

saga entitled Gísla

saga (Gisli Surssons Saga). The events take place from

940-980, but the saga itself was written around 1270-1320. Two written

versions of the saga exist, one of which is translated by Martin S. Regal.

However, there are slight deviations throughout the film. The role of Gislis

dreams seems unimportant throughout the course of the film until the final

battle between Gisli and his hunters, but in the saga his dreams played a bigger

role in predicting his fate. Also, the saga did not give faces to the women

portrayed in Gislis dreams. The film, however, depicts the good dream woman

as Gislis wife and the bad dream woman as his sister. This may have been done

in the film to ensure that the audience realized the critical roles that the

women played in the course of events in the story

| - - - - - - - -

Harald Fairhair

- (c. 850 c. 933), son of Halfdan

the Black, was the first king (872930) of Norway.

...

In 866, Harald made the first of a series of conquests over the many petty

kingdoms which would compose all of Norway, including Värmland

in Sweden, which had sworn allegiance to the Swedish king Erik

Eymundsson.

In 872, after a great victory at Hafrsfjord near Stavanger, Harald found himself king over the whole country. His realm was, however, threatened by dangers from without, as large numbers of his opponents had taken refuge, not only in Iceland, then recently discovered; but also in the Orkney Islands, Shetland Islands, Hebrides Islands, Faroe Islands and the northern European mainland.

However, his opponents' leaving was not entirely voluntary. Many Norwegian chieftains who were wealthy and respected posed a threat to Harald; therefore, they were subjected to much harassment from Harald, prompting them to vacate the land. At last, Harald was forced to make an expedition to the West, to clear the islands and the Scottish mainland of some Vikings who tried to hide there

History of Iceland

- The first permanent settler in Iceland is usually considered to have

been a Norwegian chieftain named Ingólfur

Arnarson. he settled with his family around 874, in a place he named Reykjavík

(Cove of Smoke) due to the geothermal steam rising from the earth.

...

Ingólfur was followed by many more Norse chieftains, their families and

slaves who settled all the inhabitable areas of the island in the next decades. These

people were primarily of Norwegian,

Irish and Scottish

origin. Some of the Irish and Scots were slaves and servants of the Norse chiefs

according to the Icelandic

sagas and Landnámabók

and other documents.... The traditional explanation for the exodus from Norway

is that people were fleeing the harsh rule of the Norwegian king Haraldur

Hárfagri (Harald the Fair-haired), whom medieval literary sources

credit with the unification of some parts of modern Norway during this period. It

is also believed that the western fjords of Norway were simply overcrowded

in this period.

...

In 930, the ruling

chiefs established an assembly called the Alþingi

(Althing). The parliament

convened each summer at Þingvellir,

where representative chieftains (Goðorðsmenn

or Goðar) amended laws, settled disputes and appointed juries to judge

lawsuits. Laws were not written down, but were instead memorized by an elected Lawspeaker

(lögsögumaður). The Alþingi is sometimes stated to be the world's

oldest existing parliament. Importantly, there was no central executive

power, and therefore laws were enforced only by the people. This gave rise to blood-feuds,

which provided the writers of the Icelanders'

sagas with plenty of material.

| - - - - -

Another aspect to this is that many "dispossessed" young men were recruited into the Christian religion ... Were the Utlagi exiles of King Edwy young monks of Saint Dunstan? and being of Viking ancestry fled to friendly viking Dublin Ireland?

Utlagi - INFORMATION TO USERS - azu_td_9534686_sip1_m.pdf

OF SAGAS AND SHEEP:

TOWARD A HISTORICAL ANTHROPOLOGY OF SOCIAL CHANGE AND PRODUCTION FOR MARKET, SUBSISTENCE AND TRIBUTE IN EARLY ICELAND (10TH TO THE 13TH CENTURY)

by Jon Haukur Ingimundarson

A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLGY

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA

1995

...

CHAPTER 9: A GOLD RING ON A BLOODY HAND. ON EPISODE THREE AND EPILOGUE OF BJARNAR SAGA HITDRLAKAPPA 242

...

The most common words for an outlaw in the family sagas are utlagi ("outlaw"; plural utlagar) and utilegumaour ("lying

out man"; plural utilegumenn) (Amory 1992). I will discuss the significance of Bjarnar saga's legalistic term for

outlaws in a moment.

...

The Icelandic family sagas do not make direct references to Icelandic cloisters and monks, which makes

sense since there were no monasteries in Iceland in the socalled "sagatime" (sogutimi), the period which is the family

stage (9th to the early 11th century).

The first cloisters in Iceland were established at ~ingeyrar (Southwest) in

1112, ~vera (Northwest) in 1155, and in Hitardalur in 1166-soon followed by the short lived monasteries on Flatey

island (1172-1184), about which little is known, and in 1181, the long-lasting, influential and literary-productive

Helgafell monastery. The last two mentioned monasteries were situated near Hitardalur to the north.

My idea that Bjarnar saga's evokes the knowledge of cloister-life in Hitardalur is not simply based on the

reference to virki. Bjorn's skogarmenn, who built the virki, calls forth the term

utlagi ("outlaw" or "outlying"),

with its multiple meaning assignments. It is possible that a saga writer, perhaps a

clergyman, replaced ultlagar--the

term Icelandic oral tales and family sagas use--with the legalistic skoqarmenn, when recording or putting together

the numerous tales about Bjorn Hitdaelakappi. The use of the word skogarmenn in place of

ultlagar leads to less direct

blasphemous comparison and identification of monastics with outlaws, i.e. a blasphemous portrayal of monastic persons,

their peculiar perceived roles in society, humble dispossessory backgrounds, and evasive status with respect

to secular/civil law.

In any case, I am interested in the concept of the "outlaw" as storytellers applied it for their subversive

depiction of social categories (perceived as anti-social in some sense) other than skogarmenn, i.e. the

men who by a

legal judgement at althing were expelled from the country, or were forced to live in hiding and sometimes as killers for

hire--see Amory 1992). I will argue that the outlaw representation of those who built Bjorn's virki and stayed

with him puts the finger on a disguised intelligent analysis of certain facts about the life and status of monastics in

an Icelandic farming community.

In her book Culture and History in Medieval Iceland, Kirsten Hastrup notes about conceptual structures an

equation between the law (log) and society, and an opposition between 'the social',or the 'inside', and 'the

wild', or the 'outside'. "Outlaws were absorbed into 'the wild', actually and conceptually," she says (1985:142). She

points out that log (the law) derives from leggja (to lay down), so law was what was 'laid down' (1985:11).

Therefore, according to Hastrup, utlagar were conceptualized both as 'lying out' in the wild and outside the law or

society.

...

I will therefore elaborate on Hastrup's analysis of medieval Icelander's "conceptual structures," with regard to 'outside' vs. 'inside', law equals society/community, and the position of

utlagi. I will make the argument that creators of Bjarnar saga applied the concepts utlagi (outlaw) and

utlaegur (outlawed) creatively--in order to convey ironic messages and express their critical social analysis.

First it should be said that storytellers must have been aware of the social fact that influential, affluent or

well connected individuals who committed serious transgressions against the law/society might not receive the

punishment of becoming full outlaws.

On this, Bjarnar saga provides a example: when ~6r&ur and Kalfur

escape the

punishment of full outlawry, because they were able to pay a hefty fine instead, and because the powerful

~orkell

Eyj6lfsson's condition before the judgement was that his friend ~6r~ur should be

allowed to able to pay for his crime

by way of "wealth-payment" (fegjald), instead of being forced to leave the

country. In agreement with the above

observation and social fact was the realization that individuals would become legal outlaws only if they had

always been outlaws in another, non-legalistic sense, i.e. individuals who were without substantial alliance support,

those who were dispossessed, disinherited or excluded in one way or another from (while living within) community/society.

Now, my main concern is to show that monastic figures, including Bjorn, are depicted as outlaws in Bjarnar saga.

The very existence of ecclesiastics, monks in particular, invited storytellers to apply a cynical understanding of

"outlaw" and "outlawry" in order to describe, analyze, and explain their origins, statuses, and peculiar positions

within Icelandic farming communities. For one thing, it must have been observed that

a number of clergymen and monks

rose from the class of the lower peasantry, had been disinherited, or were illegitimate

children. In resemblance

to the legal utlagi, they were to leave their farm and family of origin, worldly community, and abandon possessions

and their former intimates. Of course, as I have pointed out earlier, ecclesiastical establishments must have been

quite integrated into, instead of isolated from the surrounding community of farming households. But similarly,

in spite of their received sentence, many outlaws would remain in hiding in Iceland, with intimates who aided and

harbored them, or district leaders who used their services as part of fulfilling their political ambitions (Amory

1992).

The use of a figure of "outlaw" to represent monastics in Bjarnar saga is clearly contingent on the observation

that "God's servants" (bj6nar drottins) did not view themselves as having to answer to secular authority, a

living within the framework of civil law/ordinary society.

Comparing monastics to outlaws was inspired by the fact that outlaws who did not leave Iceland, survived by acting outside the framework of secular law, and often performed,

as Amory suggests, "dirty deeds" (illvirki) on the behalf of politically-powerful families (who had the law in their own

hands) in return for material support and protection.

Thus I have built an argument for the analysis that the sk6garmenn who, according to rumor, built

Bjorn's fortress

refer to monks who performed services which Bjorn preceded over while he protected them. Bjorn's obscure men or

servants were in fact cloaked in two senses of that word (in cowls and under veil).

The making of a fortified circle

around Bjorn's farm at H6lmur, and his dominance within this circle or religious order--where he is portrayed,

interestingly enough, with a company thirty armed men over one Christmas celebration--marks the beginning of the end

for Bjorn. Since the mass on second day of Christmas is sung at H6lmur, we can read between the lines that Bjorn has

abandoned the church at Vellir in favor of another type of holy establishment at H6lmur, a fortified one. Bjorn has

made the transition from being a consecrated churchwarden to an obscure abbot and prior.

The use of the legal term for outlaws to describe Bjorn's obscure resident followers stems from the fact that members of monastic orders--unlike the

clergymen on private church farms--in some ways stood protected from the secular law code, outside the borders of

ordinary society. At the same time, Bjorn's "outlaws" reside inside a protective circle, the circular fortress;

they are the ultimate insiders who live outside the law and above the society.

| - - - - -

So here is more evidence that St. Dunstan was recruiting young monks for the clergy - for good or bad, he brought the Benedictine order to England under the reign of King Edgar. Priests stripped of wife and family would be completely dependent upon the church and would be much more obedient to Rome. Interestingly, this was still not enough for Rome. In 1066, William the conqueror was given permission from the Pope to invade England and with him he brought Norman priests even more loyal to the pope (William was borrowing money from everyone even the Pope/Lombards).

Also another example of Britains' early worship of Mary Magdalene and Lazarus prior to the crusades (This was a Norman church built just after the conquest and prior to the crusades (and against the Cathars), The Normans of France certainly had exposure to the Cathars of Provence, France.

The Cathers Language: Occitan language is a Romance language spoken in southern France, Italy's Occitan Valleys, Monaco, and Spain's Val d'Aran: the regions sometimes known unofficially as Occitania. It is also spoken in the linguistic enclave of Guardia Piemontese (Calabria, Italy). Related - The Cat People: Catalan language

Linguistic

map of Occitania

Linguistic

map of Occitania

Notice also that Glastonbury was occupied with priests from Ireland:

The collected historical works of Sir Francis Palgrave

Chichester Cathedral - The Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity, otherwise called Chichester Cathedral, is the seat of the Anglican Bishop of Chichester. It is located in Chichester, in Sussex, England. It was founded as a cathedral in 1075, when the seat of the bishop was moved from Selsey... Chichester Cathedral was built to replace the cathedral founded in 681 by St. Wilfrid for the South Saxons at Selsey. The seat of the bishop was transferred here in 10

Selsey was the capital of the South Saxons kingdom, possibly founded by Ælle. Wilfrid arrived circa 680 and converted the kingdom to Christianity, as recorded by the Venerable Bede.[22] Selsey Abbey stood at Selsey (probably where Church Norton is today),[23] and was the cathedral for the Sussex Diocese until this was moved to Chichester in 1075 by order of William the Conqueror

139

Dunstan, Abbot of Glastonbury, had, at an early period of his

life, been admitted into that ancient monastery, which was then also a school or

college. Glastonbury was principally filled

by Scots, or monks from Ireland.

...

The popes of Rome were, about this time, most earnest in compelling the celibacy

of the clergy. In the Anglo-Saxon empire, this regulation had never yet been

enforced upon the inferior orders of the hierarchy. The principle upon which

the prohibition was founded, arose from a mistaken application of passages of

Scripture, appearing, when separated from their context, to justify a

restriction, which, if imposed as a yoke upon men's consciences, was wholly in

contradiction to the spirit of the Gospel. Considered, however, as a matter of

discipline and expediency, there were reasons of policy which might then render

it in some degree advisable. In the middle ages, when all the institutions of

society had a strong tendency to the establishment of hereditary right, and when

there was little written law, any usage or custom which had subsisted for two or

three generations, easily acquired the validity of positive legislation. Lands

had been granted to the clergy for their maintenance. A married priesthood would

soon have degenerated into a caste of sacerdotal nobility, holding their lands

as a patrimonial inheritance by the nominal condition of serving at the altar, but neglecting, in

fact, every duty which they were charged to perform.

143 Benedictine Order

955-973

At an earlier period, this state of things had been sufficiently realized in Northumbria, to shew the nature and extent of the imminent danger by which the church was threatened. If the system had prevailed, the spiritual ministration of religion would have been debased, the temporal advantages resulting to the community from the establishment of Christianity would have been wholly destroyed; therefore, we can well suppose, that many thinking men, honestly anxious for the real interests of religion, would labour for the prevention of such an abuse. Most closely connected with this question of celibacy, was the introduction of the Benedictine rule among the monks of England1.

Before Dunstan's time, each congregation of recluses lived according to its own internal regulations, nor were the several monasteries consolidated into one community.

A Roman of the name of Benedict, a man of sincere piety, had introduced a new code into the monastery which he founded upon Monte Cassino, in the ancient territory of the Samnitesa. Amongst much that was trifling, it contained more that was well adapted to increase the utility of the monastic life, and to restrain its vices, being particularly adapted to prevent the cloister from becoming a nestling place of sloth and profligacy. These monasteries, upon the continent, had united into one corporation.

The Benedictines of Italy were members of the same body as the Benedictines of Gaul. They were exempted from the jurisdiction of the bishops, and placed under a "General" of their own; and they soon became the ready instruments of papal

ambition.

The great object sought by the popes was the suppression of the independence of the different national churches of Christendom; and the celibacy of the clergy became a party badgea pledge of submission to the Church of

Rome, if yielded,a token of hostility, if refused. And in this spirit of conquest did Dunstan, and those who co-operated with him, engage in the plans which they pursued.

The Scottish or Irish, and Pictish and British churches, though in communion with Rome, were still independent of the papal

see. The Anglo-Saxon church was more inclined towards subjection, and the Benedictine rule had been introduced at Glastonbury. Yet the opposition was very strong.

...

146

The married clergymen, who refused to separate from their wives, were driven out by main force. Some, perhaps, were bribed into compliance by the king's [ Edgar ] bounty. As soon as a body of monks was established in any given church, large and ample donations were bestowed upon the new colony.

Such of the old English monks as had not yet received the Benedictine rule, were induced to fraternize with Monte

Cassino, either by approbation of the real merits of the systemfor merits it certainly hador in order to conciliate the king. During the Danish invasions and the consequent troubles, many of the endowments of the monasteries had been seized or acquired by the nobles and other laymen. Edgar often succeeded in persuading these persons to restore the property, which they could not hold with a good conscience. In other instances, if a stubborn "thane" resisted the persuasions of the monarch, and had made up his mind to despise the anathemas denounced against the usurpers of church property, Edgar purchased the land with his own money, and restored it to the church.

By these means, before the close of the reign of Edgar, forty-eight opulent Benedictine monasteries of monks and nuns were established in Anglo-Saxon

Britain; and these subsisted until the era fatal to all similar foundations.

Of Runes and Ogham:

Ogham links to Pembrokshire: There are some four to five hundred surviving ogham inscriptions throughout Britain and Ireland with the largest number appearing in Pembrokeshire.

Notice that Ogham are generally Celtic , while Runes are generally Nordic. In the following maps the Ogham and Runes rarely overlap. But in the book Greeks and Goths a study on the runes the idea is that Ogham replaced Runes in England and Ireland and that the Ogham are the later representations.

R. I. Page - Raymond Ian Page (25 September 1924 10 March 2012) was a British historian of Anglo-Saxon England and the Viking Age, and a renowned runologist who specialized in the study of Anglo-Saxon runes.

Runes And Runic Inscriptions (David Parsons-Carl T. Berkhout) (London-1998)

Our archaeologists and metal detectors continue to find new inscriptions with high frequency. The tentative distribution

maps I produced in 1973 showing inscriptions that could be clearly localised and dated before/after 650 were out of date

by 1987 when 'New Runic Finds in England' (below, pp. 27587) was published. That article is in turn outdated.55

Bringing the two 1973 maps up to the present produces figs 1 and 2.

The pre-650 map is most dramatically changed,

with much fuller scatters of runes in East Anglia and the East Midlands and an outlier further north. East Anglia is also

more prominent in the post-650 map than it was in 1973, and it is obvious that this region must be given more attention

in any future discussion of English runes. What cannot be shown on any of these maps is the significance of the coin

evidence, for I do not know how that could be presented. Suffice it to point to the increased weight that new discoveries

have given to East Anglian and Kentish runic coins. Two considerations make the new maps no more definitive than

their earlier versions. (i) the dividing date of 650 is, as I have said, one of convenience rather than

principle. Above I

give examples of problems of setting close dates to English runic monuments. 650 seems to work as a dividing line, but

that is all that can be said for it. (ii) the maps remain tentative. For instance, I attribute three inscriptions to Brandon in

my later map but only two, I think, can be put clearly post-650. The third, on a bone handle, is included by association.

Again, I have not added the Worcester find to the later map though I suspect it properly belongs there. That might be

established in a formal excavation report. It would be an intriguing addition.

The past few years have brought an upsurge of interest in Anglo-Saxon runic studies, in part because of the entry to the

field of distinguished younger scholars. I hope the present collection helps by giving something of the background to

English runic research. The papers have been reprinted without major changes.

...

| - - - - -

Interesting comments about Ogham replacing Rune Stones in Pembrokeshire:

Greeks and Goths a study on the runes - Isaac Taylor - 1879

18. The Oghams.

The Scandinavian settlers in Northumbria, Cumbria, and the Isle of Man, having left behind them so many runic records of their presence,

it may seem strange that not a single runic stone should have been discovered in the Scandinavian colony of Pembroke, or even in Ireland, where Scandinavian chieftains bore sway for many years in the cities of Dublin, Waterford, and Limerick.

The runic treasures of Wales and Ireland are limited to one small silver coin, struck in Dublin, which bears a runic legend1. But the fact of this remarkable absence of runic monuments in certain regions where they might have been looked for, must be taken in conjunction with another circumstance, equally remarkable, that it is exactly in those regions where the expected runic stones are wanting that Ogham stones abound. These facts will be explained if it can be established that the mysterious Ogham character, in which

1 Worsaae, Danes and Norwegians, p. 338.

Replacement of Runes by Oghams. 109

the most ancient records of Wales and Ireland are written, and respecting which so many wild conjectures have been made, was originally nothing more or less than a very simple and obvious adaptation of the Futhorc to xylographic necessities, the individual runes being expressed by a convenient notation consisting of notches cut with a knife on the edge of a squared staff, instead of being cut with a chisel on the surface of a stone. Some such method of notation seems to be implied by the words book and buch-staben (beech sticks), and may probably be referred to in the often quoted lines of Venantius Fortunatus, a sixth century poet, who says,

Barbara fraxineis pingatur rhuna

tabellis, Quodque papyrus agit, virgula plana valet.

The geographical distribution of the Ogham inscriptions raises a strong presumption in favour of the Scandinavian origin of the Ogham

writing.

The Ogham districts of Wales and Ireland were, without exception, regions of Scandinavian occupancy.

As I have elsewhere pointed out1, the existence of a very early Scandinavian settlement in Pembrokeshire is indicated by a dense cluster of local names of the Norse type which surrounds, and radiates from, the fiords of Milford and Haverford. The Ogham district in Wales is nearly conterminous with the limits of this Scandinavian colony as determined by the local names.

Seventeen out of the twenty Welsh Ogham inscriptions are in the counties of Pembroke, Cardigan, Carmarthen, and Glamorgan, nine out of the seventeen being in Pembrokeshire itself.

There are also two Ogham inscriptions in Devon, and one in Cornwall, and there are said to be one or two in Scotland1. But of the extant Ogham inscriptions more than five-sixths are in Ireland, and these, with four or five exceptions, are found along that part of the Irish coast which lies opposite to the Scandinavian colony in Pembroke, and which, as is attested by such local names as Waterford and Smerwick, was frequented and settled by the Northmen.

No less than 148 out of the 155 Irish Oghams are found in the four counties of Kilkenny, Waterford, Cork, and Kerry1, or, roughly speaking, they fringe the line of coast which stretches between the two Scandinavian kingdoms of Waterford and Limerick.

It may safely be affirmed that where the Northmen never came Ogham inscriptions are never

found.

Ogham -- Ancient History Encyclopedia

One of the stranger ancient scripts one might come across, Ogham is also known as the Celtic Tree Alphabet. Estimated to have been used from the

fourth to the tenth century AD it is believed to have been possibly named after the Irish god Ogma but this is debated widely. Ogham actually refers to the characters themselves, the script as a whole is more appropriately named Beith-luis-nin after the order of alphabet letters BLFSN.

Description

The script originally contained twenty letters grouped into four groups of five. Five more letters were later added creating a fifth group. Each of these groups was named after its first letter.

There are some four to five hundred surviving ogham inscriptions throughout Britain and Ireland with the largest number appearing in

Pembrokeshire. The rest of the inscriptions were located around south-eastern Ireland, Scotland, Orkney, the Isle of Man and around the border of Devon and

Cornwall. Ogham was used to write in Archaic Irish, Old Welsh and Latin mostly on wood and stone and is based on a high medieval Briatharogam tradition of ascribing the name of trees to individual characters.

The inscriptions containing Ogham are almost exclusively made up of personal names and marks of land ownership.

Origin Theories

There are four popular theories discussing the origin of Ogham. The differing theories are unsurprising considering that

the script has similarities to ciphers in Germanic runes, Latin, elder futhark and the Greek alphabet.

The first theory is based on the work of scholars such as Carney and MacNeill who suggest that Ogham was first created as a cryptic alphabet designed by the Irish. They assert that the Irish designed it in response to political, military and/or religious reasons so that those with knowledge of just Latin could not read it.

The second theory is held by McManus who argues that Ogham was invented by the first Christians in early Ireland in a quest for uniqueness. The argument maintains that the sounds of the primitive Irish language were too difficult to transcribe into Latin.

The third theory states that the Ogham script from invented in West Wales in the fourth century BC to intertwine the Latin alphabet with the Irish language in response to the intermarriage between the Romans and the Romanized Britons. This would account for the fact that some of the Ogham inscriptions are bilingual; spelling out Irish and Brythonic-Latin.

The fourth theory is supported by MacAlister and used to be popular before

other theories began to overtake it. It states that Ogham was invented in

Cisalpine Gaul around 600 BC by

Gaulish Druids who created it as a hand signal and oral language. MacAliser

suggests that it was transmitted orally until it was finally put into writing in

early Christian Ireland. He argues that the lines incorporated into Ogham

represent the hand by being based on four groups of five letters with a sequence

of strokes from one to five. However, there is no evidence for MacAlisters

theory that Oghams language and system originated in Gaul.

...

BabelStone The Ogham Stones of the Isle of Man

The Isle of Man, situated midway between Ireland and Britain, has always been at a sea-faring crossroads, and over the centuries has been exposed to influences from many different cultures. This is well reflected in the relatively large number of monumental inscriptions that have survived on the island, which include both runestones and Ogham stones, exhibiting a mixture of Irish, British, Pictish and Norse influences.

BabelStone - The Ogham Stones of Wales

Wales has the greatest number of Ogham stones of any region outside of Ireland (35 stones with definite Ogham inscriptions), but as can be seen from the map below, they are unevenly distributed, with large numbers in the south-west and the south-east, and only a handful in the north :

Location of Ogham stones and other Ogham-inscribed objects (England, Wales, Scotland and the Isle of Man are now complete; Ireland will be added by the end of Summer 2010.

Red tags mark the sites of

certain Ogham inscriptions (a dot indicates that the stone is in situ)

Yellow tags mark the sites of

dubious or unconfirmed Ogham inscriptions

Blue tags mark museums or

other sites where Ogham stone are held

Very important information about

early law "The All Thing" (Thing for All the land) and how a breech created a "wolf in the

sanctuary"

Notice the connection of "The Thing" to -> "All Thing" -> Althing -> Atheling - a prince of any of the royal dynasties .

Notice how both Runes and Ogham script is related to Greek alphabet and that Saxons were also Northmen that were considered remnants of Alexander the Greats' Greek Army. Alexander in his conquests went about collecting all the secret knowledge of the eastern conquests he could. The Hebrews may well have been liberated by Alexander from bondage of the Babylonians.

The Viking Age - the early history, manners and customs of the ancestors of the English-speaking nations - PAUL B. DU CHAILLU

The Viking Age- the early history, manners, and customs...

ORIGIN OF NAME ENGLAND. 19

That the history of the people called Saxons was by no means certain is seen in the fact that

Witikind, a monk of the tenth century, gives the following account of what was then considered to be their origin 1 :

" On this there are various opinions, some thinking that the Saxons had their origin from the Danes and Northmen ;

others, as I heard some one maintain when a young man, that they are derived from the Greeks, because they themselves used to say the Saxons were the remnant of the Macedonian army, which, having followed Alexander the Great, were by his premature death dispersed all over the world."

...

In the Sagas the term England was applied to a portion only of Britain, the inhabitants of which were called

Englar,

Enskirmenn. Britain itself is called Bretland, and the people

Bretar.

...

[The Promises to the Fathers - Truth in History

- Now Bret-land means literally covenant-land, or the land

of the covenant, as Britain means the island of the covenant. Here are two

witnesses in the ancient names of this land indicating that it is the land of

the covenant promised for the planting of Israel in the covenant which God made

with David, and the island of the covenant according to the descriptions

of the islands in the west at the ends of the earth as given by Isaiah. But,

in addition to this, consider the following truths: The Hebrew word for man is

ISH. Hence BRIT-ISH means literally covenant-man, or man of the covenant. The

islands to the northwest of Britain are called Hebrides to this day. Why? How

did they get that name? The simple and rational explanation is that they were

settled and named by the Hebrews. ]

It is an important fact that throughout the Saga literature describing the expeditions of the Northmen to England

not a

single instance is mentioned of their coming in contact with a people called

Saxons, which shows that such a name in Britain was unknown to the people of the North. Nor is any part of England called Saxland.

OUTLAWRY. 578

Irredeemable crimes Outlaws regarded as enemies of society Custom of pleading for an outlaw Liabilities of a murderess Substitution of corporal punishment and fines for outlawry Purchase of an outlaw's peace.

THE laws did not aspire to improve the moral condition of the criminal and try to make him a better man, except through

fear of punishment ; their object in early days was to prevent private revenge, and stop people taking matters into their own hands. Crimes against personal rights or those of property were punished by fines as indemnity to the injured.

By paying an indemnity the criminal released himself from the revenge of the injured and of his family, or from the outlawry which his conduct or crime had brought upon him.

If any man had wronged another he was placed outside the pale of the law until the weregild was paid ; and if he or his family could not pay he was outlawed, and the outlawry was declared at all the Things in the

country.

...

BUYING PEACE FROM THE KING. 583

If a man was outlawed he had to buy his peace, "fridkaup," from the king, who determined what the amount should be.

[ Notice This allows an Outlaw who is a "friend" of the King to be above all - protected ]

" Now it may happen that the king permits the outlaw to stay in the land at the entreaties of chiefs, or in some other way. Then he (the outlaw) must buy peace with the king according to his mercy (the price paid by the outlaw to stay in peace in the country is determined by the king), and pay that half of his fine which is unpaid with sale-meetings (auctions), of the kind that men of good sense see that he is well able to hold. If he is not willing to pay, the kinsmen of the dead may take revenge on him, even though he be reconciled (in peace) with the king, and they will not be outlawed though they slay him. But those who took care of his property while he was an outlaw must pay him back as much as they received in lands and movables, and the rent of the land besides " (Frostathing's Law, Introd. 5).

SACREDNESS OF TEMPLES. 359

...

The temples were considered so holy that any one damaging them or entering them armed was declared an outlaw, and no one who had committed an offence punishable by law was allowed to enter ; such person was called Vary i Veum (wolf in the sanctuary). The grove or fields surrounding the temples were often regarded as inviolate, so that no act of violence would be permissible within their precincts. This was expressed by the ancient name of

Ve (sanctuary, sacred place), which was extended so as to embrace the T/m^-place, which was also regarded as sacred, while the Thing was going on.

THE THING . 515

The Thing was held in an open place called Thingvoll (Thing-plain), in earlier times

near a temple. 1 On the Thingvoll, or near it, there always seems to have been a

Thing-brekka, or Thing-hill, from which all announcements were made.

The Thing-plain was a sacred place, which must not be sullied by bloodshed arising from blood-feud (lieiptarblod) or

any other impurity. The Thing, from the time it was opened until it was dissolved, was during pagan times under the

protection of the gods. It was opened with certain religious ceremonies, which included a solemn peace declaration (grida

seining) over the assembly, which in earlier times was pronounced by the Hersir near whose temple the Thing took

place. Every breach of the peace at a Thing was a sacrilege which put the guilty one out of the pale of the law he was

like the violator of the temple peace a varg i veum (wolf in the

sanctuary), an outlaw in all holy or inhabited places, and an utlagi (outlaw) for all until he had made reparation

for his crime.

Reference: Anne-Christine-Larsen-the-vikings-in-ireland.pdf

The Vikings in Ireland - Anne-Christine Larsen

- Viking Ship Museum, Dec 30, 2001 - 172 pages

This compilation of 13 papers by scholars from Ireland, England and Denmark, consider the extent and nature of Viking influence in

Ireland. Created in close association with exhibitions held at the National Musem of Ireland in 1998-99 and at the National Ship Museum in Roskilde in 2001, the papers discuss aspects of religion, art, literature and placenames, towns and society, drawing together thoughts on the exchange of culture and ideas in

Viking Age Ireland and the extent to which existing identities were maintained, lost or assimilated.

In the late 12th-century Dublin roll of names Scandinavian personal names only make comparatively rare appearances. Among those to appear most frequently are a number of compound names in Thor-: Turold, Turbeorn, Torpin (Thorfin), Thur -got, Turkil, Thurstein and the short form Toki. All these names were also in common use in the Nordic homelands. The only signs of Irish-Nordic creative initiative among the names in the Dublin roll are the forename Iarnfin, an otherwise unrecorded compound, and the by-names Utlag outlaw, borne by Torsten and Reginaldus, and the partially anglicised Vnnithing undastard, borne by Philippus.

Very exciting - Geat's - Wuffing Utlage evidences: Rune stones, Ballstorp, Edsvära, Västergötland, Sweden and Smaland

700~1000AD - Útlagi placed this stone in memory of Sveinn -Rune sm103 - Småland

Sutton Hoo-The Evidence of the Documents By J. L. N. O'LOUGHLIN - Bjorkman, while in no doubt that the Wylfings were to be localized in southern Sweden, hazarded the conjecture that, if the Wylfings were not, in fact, Geats (Gotar}, their most probable home was in Blekinge. He then identified them with the Gothic Wulfings, the Heruli, who were known to have settled in southern Sweden, in Blekinge or in southern Smaland, on their return from southern Europe.

990~1010AD - Utlage raised this stone in memory of Eyvindr, a very good thegn - vg62 Ballstorp, Edsvära, Västergötland, Sweden

English: Men at a rune stone (Vg 62) in Ballstorp, Edsvära. - This rune stone was used as building material in a bridge in Ballstorp. It was rediscovered in 1900, and in the following year it was raised next to the old church ruin. There is a modern text written with runes on the back of it : tina stin ar hita ok rist or MCCCCI af Ioan fron Stomin - This stone is found and raised in 1901 by Johan from Stommen

The inscription says:

"Utlage raised this

stone in memory of Öjvind, a very good thegn".

A "thegn" might be a peasant proprietor, yeoman or a warrior .

Parish (socken): Edsvära

Province (landskap): Västergötland

County (län): Västra Götaland

Rune stone, Ballstorp, Edsvära, Västergötland, Sweden

Flickr Swedish National Heritage Board's Photostream

Västergötland - There are many ancient remains in Västergötland. Most prominent are probably the dolmens from the Funnelbeaker culture, in the Falköping area south of lake Vänern. Finnestorp, near Larv, was a weapons sacrificial site from the Iron Age.[3]

The population of Västergötland, the Geats appear in the writings of the Greek Ptolemaios (as Goutai), and they appear as Gautigoths in Jordanes' work in the 6th century.

The province of Västergötland represents the heartland of Götaland, once an independent petty kingdom with a long line of Geatish kings. These are mainly described in foreign sources (Frankish) and through legends. It is possible that Västergötland had the same king as the rest of Sweden at the time of the monk Ansgar's mission to Sweden in the 9th century, but both the date and nature of its inclusion into the Swedish kingdom is a matter of much debate. Some date it as early as the 6th century, based on the Swedish-Geatish wars in Beowulf epos; others date it as late as the 12th century.

Runes in Sweden

Runes in Sweden

Rune stone, Ballstorp, Edsvära, Västergötland, Sweden Flickr -... (via Instant Mobilizer)

Here is how the rune stone looks today.: Vg 62 - Västergötland Ballstorp, Edsvära

Ballstorp VG62 -

Útlagi raised this stone in memory of Eyvindr, a very good Þegn.

Ballstorp VG62 -

Útlagi raised this stone in memory of Eyvindr, a very good Þegn.

This rune stone was used as building material in a bridge in Ballstorp. It was rediscovered in 1900, and in the following year it was raised next to the old church ruin. There is a modern text written with runes on the back of it :

tina stin ar hita ok rist or MCCCCI af Ioan fron Stomin - This stone is found and raised in 1901 by Johan from Stommen

Runestone - is typically a raised stone with a runic inscription, but the term can also be applied to inscriptions on boulders and on bedrock. The tradition began in the 4th century, and it lasted into the 12th century, but most of the runestones date from the late Viking Age. Most runestones are located in Scandinavia, but there are also scattered runestones in locations that were visited by Norsemen during the Viking Age. Runestones are often memorials to deceased men.

Runestones were usually brightly colored when erected, though this is no longer evident as the color has worn off.

| - - - -

Runic Dictionary inscription Vg 62 - (link page contains a map) - Rundata

period/dating: V - V, meaning Viking

Age, which is very broad spanning the late 8th to 11th centuries

style group: RAK -- ca. 990-1010 AD

english: Útlagi

raised this stone in memory of Eyvindr, a very good Thegn.

Interstingly Eyvindr was a name used by a man of court to the King of Norway Haakon I of Norway in the time period and notice that Oslo is not too far away and the time period is correct, and there is a connection to England's King Athelstan - Eyvindr Skáldaspillir :

Haakon I of Norway - (c. 920961), given the byname the Good, was the third king of Norway and the youngest son of Harald I of Norway and Thora Mosterstang

King Harald determined to remove his youngest son out of harm's way and

accordingly sent him to the court friend, King Athelstan

of England. Haakon was fostered by King Athelstan, as part of a peace

agreement made by his father, for which reason Haakon was nicknamed Adalsteinfostre.[2]

The English king brought him up in the Christian

religion. On the news of his father's death King Athelstan provided Haakon

with ships and men for an expedition against his half-brother Eirik

Bloodaxe, who had been proclaimed king.

...

Haakon I was

frequently successful in everything he undertook except in his attempt to

introduce Christianity,

which aroused an opposition he did not feel strong enough to face. So entirely

did even his immediate circle ignore his religion that Eyvindr

Skáldaspillir, his court poet,

composed a poem, Hákonarmál,

on his death representing his welcome by his ancestors' gods into Valhalla.

Eyvindr Skáldaspillir - was a 10th century Norwegian skald. He was the court poet of king Hákon the Good and earl Hákon of Hlaðir. His son Hárekr later became a prominent chieftain in Norway.

His preserved works are:

Eyvindr drew heavily on earlier poetry in his works. The cognomen skáldaspillir means literally "spoiler of poets" and is sometimes translated as "plagiarist", though it might also mean that he was better than any other poet. He's mentioned in the second verse of the Norwegian national anthem.

| - - - - - - -

Runic Dictionary manuscripts search Utlag

Runic Dictionary inscription Sm 103 - Now this is in Wulfing territory:

Sweden:

Småland

Location: Rösa, Skede sn, Östra hd;

period/dating: V - V, meaning Viking

Age, which is very broad spanning the late 8th to 11th centuries

(700-1000AD)

english: Útlagi placed this stone in memory of Sveinn

The small lands of Småland. The black and red spots indicate runestones. The red spots indicate runestones telling of long voyages.

Småland

- is a historical province

(landskap) in southern Sweden.

Småland borders Blekinge,

Scania or Skåne,

Halland, Västergötland,

Östergötland

and the island Öland

in the Baltic

Sea. The name Småland literally means Small Lands.[2]

The latinized

form Smolandia

has been used in other languages. The highest summit in Småland is Tomtabacken

with its 377 m

Småland

- is a historical province

(landskap) in southern Sweden.

Småland borders Blekinge,

Scania or Skåne,

Halland, Västergötland,

Östergötland

and the island Öland

in the Baltic

Sea. The name Småland literally means Small Lands.[2]

The latinized

form Smolandia

has been used in other languages. The highest summit in Småland is Tomtabacken

with its 377 m

...

The name Småland ("small lands") comes from the fact that it

was a combination of several independent lands, Kinda (today a part of Östergötland),

Tveta, Vista, Vedbo, Tjust,

Sevede, Aspeland, Handbörd, Möre,

Värend, Finnveden

and Njudung. Every small land had its own law in the Viking age and early

middle age and could declare themselves neutral in wars Sweden was involved in,

at least if the King had no army present at the parliamentary debate. Around

1350, under the king Magnus

Eriksson a national law was introduced in Sweden, and the historic provinces

lost much of their old independence.

The city of Kalmar is one of the oldest cities of Sweden, and was in the medieval age the southernmost and the third largest city in Sweden, when it was a center for export of iron, which, in many cases, was handled by German merchants... IKEA was also founded in the Småland city of Älmhult

8_001_019 Sutton Hoo-The Evidence of the Documents By J. L. N. O'LOUGHLIN - Bjorkman, while in no doubt that the Wylfings were to be localized in southern Sweden, hazarded the conjecture that, if the Wylfings were not, in fact, Geats (Gotar}, their most probable home was in Blekinge. He then identified them with the Gothic Wulfings, the Heruli, who were known to have settled in southern Sweden, in Blekinge or in southern Smaland, on their return from southern Europe.

Götaland - Gothia, Gothland,[1][2] Gothenland, Gautland or Geatland is one of three lands of Sweden and comprises provinces.... Götaland once consisted of petty kingdoms, which its inhabitants called Gautar in Old Norse. It is generally agreed that these were the same as the Geatas, the people of the hero Beowulf (8th11th century) in England's national epic by the same name.

Blekinge

- is one of the traditional provinces

of Sweden (landskap), situated in the south of the country. It

borders Småland,

Scania and the Baltic

Sea. It is the country's second-smallest province by area (only Öland

is smaller), and the smallest province located on the mainland.

... Blekinge became part of the kingdom of Denmark

at some point in the early 1000s - most likely 1026.

Its status before then is unknown

Blekinge

- is one of the traditional provinces

of Sweden (landskap), situated in the south of the country. It

borders Småland,

Scania and the Baltic

Sea. It is the country's second-smallest province by area (only Öland

is smaller), and the smallest province located on the mainland.

... Blekinge became part of the kingdom of Denmark

at some point in the early 1000s - most likely 1026.

Its status before then is unknown

Östergötland - The traditions of Östergötland date back into the Viking age, the undocumented Iron Age, and earlier, when this region had its own laws and kings (see Geatish kings and Wulfings). It is said that the famous Viking warrior Beowulf may likely have been from what is now the Östergötland region. The region kept its own laws, the Östgötalagen, into the Middle Ages. Östergötland belonged to the Christian heartland of the late Iron Age and early medieval Sweden. The Sverker and Bjälbo dynasties played pivotal roles in the consolidation of Sweden.

The province has about 50,000 ancient remains of different kinds. Some 1,749 are, for instance, grave fields

RUNES AROUND THE NORTH SEA AND ON THE CONTINENT AD 150-700

...

Period I, the archaic period, stretches in all regions from the very beginning of runic writing to the 7th century, and it coincides everywhere with the pre-Christian era or with a transitional phase to Christianity. In historical terms this concerns the Roman and Merovingian periods. The exact beginning of Period I varies locally.

In Denmark Period I lasts from the 2nd c. to the 6th c.

In England Period I starts in the 5th and goes on to the 7th c.

Continental runic writing

stretches from the 2nd c. to the 7th c. From The Netherlands the whole runic

period has been included, from the 5th c. to the 9th c. Period II, when runic

writing appears to have become more integrated in society, began in Denmark and

England somewhere during the 7th century.

...

All runic finds from the Danish bogs and graves, approximately dating from the

period 160- 450, have been found in a context that clearly shows Roman

connections

...

3.1. The objects that were offered and buried may have been inscribed to serve

some ritual function, but this is difficult to prove, since we do not have any

unambiguous texts that would confirm such a function. It is impossible to

identify, beyond any doubt, texts that are undisputedly religious, or that refer

to the supernatural. Some scholars believe that at least

part of the runic texts are magical, simply because in their

opinion runes were basically be a magical script. Runes were

certainly used in texts that had magical purposes, such as is perhaps shown by

seemingly meaningless sequences like aaaaaaaazzznnn?bmuttt on the Lindholm bone

piece.

Forgotten Scripts By Dino Manzella

Runes were believed to be magical. Nothing but pure magic could explain the phenomenon of speaking to someone without actually being there; and to think that the message inscribed could speak to thousands of people thousands of years after it's author had died. It was mystifying. It had to be pure magic!

Kjula ås: thing

mound with rune-stone in foreground.

Photograph by A Sanmark

Viking-Age

"things" were the public assemblies of the free men and functioned as

both parliaments and courts.

There were things at different levels of society local, regional and

supra-regional and meetings were held at regular intervals as well as on an

ad hoc basis when the need arose.

The significance of these things for the functioning of Viking society is

under-appreciated, with feuding seen as the most common way of regulating

society and solving conflicts.

Certainly feuding is a regular theme in the sagas, perhaps because it serves as

an exciting literary theme, but the things role as arenas for conflict

resolution, marriage alliances, power display, honour and inheritance

settlements, etc also comes across very clearly.

...

Larsson concluded that Swedish assembly sites often had a number of typical

features: large mounds, a concentration of rune-stones and a close connection

with crossings between roads by land or water.

Brink argued that a

rune-stone, a thing mound and an ancient road (often the royal Eriksgata ) lined

by standing stones constituted a Viking Age thing assembly site or to

be more circumspect were essential elements that constituted a Viking Age

thing assembly site.

Interesting to look at other sites near VG-62 in Västergötland Sweden hmmm....

700~1000AD - Útlagi

placed this stone in memory of Sveinn -Rune sm103 - Småland,

Sweden

990~1010AD - Utlage

raised this stone in memory of Öjvind, a very good thegn -

Rune vg62 - Ballstorp, Västergötland, Sweden

| - - - -

Tanner_Gregory_Rune_Stones_and_Magnate_Farms

...

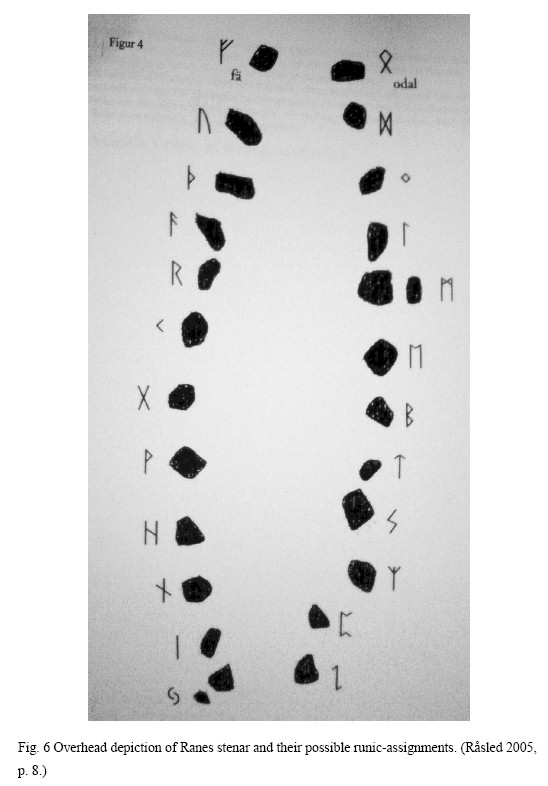

Ranes Stenar: Odins hall?

The modern site of Askeberga in Vadsbo Hundred, located approximately one kilometer to the east of Odens sjö is home to the remarkable stone monument known as Ranes stenar, or Odins Stones. The monument consists of 24 stone blocks in the form of a Viking great hall, some of which weighing up to 30 tons each. It is 55 meters long and 18 meters wide, and its construction must have taken considerable effort, organization and man-power (Lindblom 1982, p. 20).

In many contemporary sources and on current maps Ranes stenar is somewhat frustratingly often miss-referred to as a stone ship monument. There are several problems with this interpretation: To begin with, and I think the most obvious are the open ends on both ends of the hall. In all stone ship monuments, there is a prow, and stern stone, one usually being taller or larger than the other to indicate which way the ship is sailing. These are both missing at Ranes stenar (Råsled 2005, p. 1.).

Also of interest to Ranes stenar, and possibly strengthening the Valhalla/Odin cult theory is the fact there is only one other similar stone monument to it in all of Scandinavia, and it just happens to lie in Nässjä, five kilometers southwest of the town of Vadstena, directly to the east of Vadsbo Hundred on the eastern shore of Lake Vättern in Östergötland County.

Råsleds theory on the number of stones themselves and not just a similarity in their placement and form to Valhalla, which I also find very interesting and possibly strengthening as to the idea of a cult purpose being the underlying factor for the construction of the two hall monuments was thus: There are 24 stones in both of the monuments. There are 24 runes in the Elder runic alphabet. Ranes stenar is believed to have been constructed during the Iron Age so this could also seem to support a conscious connection to the earliest runic alphabet (Råsled 2005, p. 9).

Also of note in terms of an Odin cult connection is the fact that during the Viking Age it was believed that Odin himself was the creator and keeper of the runes and their magic, and the runes themselves were the key he could use to make words and make mankind speak, write, read and obey. The runes were to be feared and respected. He who kept and could write the runes also had the power of them (Råsled 2005, p.9).

...

Stone ship in Askeberga, Västergötland, Sweden. (~400-500AD) (Credit: Image courtesy of University of Gothenburg)

Askeberga

Askeberga stone ship is

one of Västergötland's most notable archaeological sites. It

is 53 meters long and the second largest in the country after Kåseberga in Skåne.

Ships are based is built

of 24 giant blob blocks of between 25 and 30 tons each.

Ships Subsidence is

typical Nordic relics consisting of standing stones made in the shape of a ship.

The size of the

formation may vary from a few meters up to 30 meters. Often

marks the stone ship a grave, but not always. The

design may also have had symbolic or ritual function.

Ships are based is often

a graveyard. It

has been dated Askeberga ship setting the Migration Period (about 400-500

e.Kr). The

place has since time immemorial been a gathering place for the people of the

district. The

oldest name of the place must have been Asgudsbäck, better known, however, Ranes

stones - Odin stones - when Rane during a period in the Lake Vänern area was a

name for Odin.

Stone Ships of Vikings - Google Groups

20. Nässja Stone Ship, Sweden

The Nässja Stone Ship located in Nässja Parish, Vadstena Municipality, Östergötland,

Sweden, measures 44×18 metres and is made of 24 large stones, of which 10 are

standing. The stone circle was excavated in 1953. One peculiarity of this

ship is that the bow and stern stones are missing. [ Because

like the study document shows it is a Hall not a boat ]

| - - - - - --

Interesting also are the Nearby England and Greece Runestones

England runestones - is a group of about 30 runestones that refer to Viking Age voyages to England.[1] They constitute one of the largest groups of runestones that mention voyages to other countries, and they are comparable in number only to the approximately 30 Greece Runestones[2] and the 26 Ingvar Runestones, of which the latter refer to a Viking expedition to the Middle East. They were engraved in Old Norse with the Younger Futhark.

Sm 101 - The Nävelsjö runestone is located at the estate of Nöbbelesholm, and it is raised in memory of a father who died in England and was buried by his brother in Bath, Somerset.

Old Norse transcription:

English translation:

Sm 104 - This fragment of a runestone is located in the atrium of the church of Vetlanda and what remains appears to say "in the west in England."

VG20 - .. raised the stone in memory of Guðmarr(?), his son, who was killed in

England.

VG187 - Geiri placed this stone in memory of Guði, his brother, who forfeited

his life in England

VG 178 - In Västergötland, there are five runestones that tell of eastern voyages but only one of them mentions Greece, used to be outside the church of Kölaby in the cemetery, some ten metres north-north-west of the belfry

English translation:

"Agmundr raised this stone in memory of Ásbjôrn, his kinsman; and Ása(?) in memory of her husbandman. And he was Kolbeinn's son; he died in Greece.

Sm 46 - was in the style RAK

English translation:

"...-vé made these monuments in memory of Sveinn, her son, who met his end in the east in Greece.

More evidence that Utlagi Vikings exiles Norway circa 870-920AD settled in Pembrokeshire (See Research page 6.) Between 866-872 Harold conquerors Norway and parts of Sweden forcing the losers to flee to other islands ....

1051 - In October Godwin and the rest of his sons were declared outlaws and given five days to leave the country. The men of Dover were left unpunished. Godwin, his wife Gytha, and his sons Swein, Tosti and Gyrth boarded ship at Bosham and left for Flanders. Harold and Leofwine Godwinson sailed from Bristol for the Norse stronghold of Dublin in Ireland.

1171 - The

people of Bristol were given Dublin as a colony by the king and many

Bristolians settled there. Charter

was issued by Henry II in 1171-1172, giving the men of Bristol the right to

live in the City of Dublin. Later charters contain grants to the city of

rights, privileges and property

--- > First record in Ireland:

1172 - Torsten

utlag - Reginaldus utlag - Dublin Roll of Names

- (First Utlag record in Ireland - Ostman or

Englishman?)

1186~1202 - Confirmation

by the Prior of St. James's, Bristol, to John, son of Ralph

Utlage, of land in Lewin's Mead

1200~1210 - Grant

by the Prior of St. James's, Bristol, to Margam Abbey, of land in Lewin's

Mead, Bristol, Formerly held by John, son of Ralph le Utlage

1210 - Margam Abbey - John, son of Ralph Utlage, of the land in the meadow of Leowine, known as Lewin's-mead, near to St. James' Church, Bristol. - dated in the early years of the thirteenth century. - Cartae et alia munimenta quae ad dominium de Glamorgancia pertinent Clark, George Thomas

| - - - - - - -

Pembrokeshire Coast National Park - Viking period

The Viking Period

The Pembrokeshire Coast lay alongside a key route for viking ships sailing

from lands to the north south towards the West Country and Europe. And with

its many natural harbours and very wealthy monasteries it received its share of

attention from the Danish and Norse traders and plunderers.

Unfortunately there is little hard archaeological evidence for viking

activities in Pembrokeshire. Our understanding is heavily based on the

extent of Norse and Danish placenames | see map historical accounts, a find of a

small norse weight at Freshwater West, and some supposition. Interestingly,

however, as a modern line of evidence, it has recently been discovered that

the occurrence of the gene for blood group A in Pembrokeshire is only matched by

parts of Scandinavia. This suggests some settlement by vikings. On the basis of

a lack of remains of viking women in the UK, these were probably men, who then

took local women as their wives.

Here are some of the events we know about:

860: Danish pirate Hubba camped on coast;

876: Norse possibly over-wintered in Milford Haven waterway with 23 ships;

893: Danes pass Pembrokeshire on way to exploits elsewhere;

902: Norse driven from Dublin may have sought land in Pembrokeshire;

914: Danes again pass by Pembrokeshire;

980-990: Raid near Solva by Olaf Tryggvason and Svein Forkbeard;

987: Celtic house on site of St Dogmaels attacked by Norse;

1080: Hedd and Isaac, sons of Bishop Abraham killed by norsemen during one of

ten raids during the period on the wooden monastic settlement at St David's

And

here is the Viking history behind some of the placenames:

And

here is the Viking history behind some of the placenames:

Caldey: from Viking name for "Cold island"

Fishguard: Before the Vikings it was known as Abergwaun

Freystrop: named after Viking goddess of fertility, Freya;

Goodwick: "Gud Vik" or fine harbour;

Hubberston: named after Hubba;

Milford Haven: derived from Scandinavian word meaning haven with sandy shores;

Ramsey: believed to be named after norseman Hrafn;

Skomer: "Skalmey" (either on account of its cloven shape or

"island of the sword"); and

Skokholm: not unlike Stockholm!

Lundy

Island, from Lundy, Isle of Avalon by Mystic Realms

Giant's Graves on Lundy island

During harvest time in 1851 islanders on Lundy discovered two immense granite

coffins, one of them said to have been ten feet long the other eight.

When these sarcophagi were opened, the excavators found the skeletons of two

eight feet tall humans, seven other skeletons of normal stature and other

assorted human bones. Either in the coffins themselves or beside them,

sources vary, were found some pale blue stone beads and some fragments of

pottery. The date attributed to the beads, and also the graves, is anywhere

from Roman times to the 14th century. The beads were apparently sent to

Bristol Museum but there seems to be no record of what happened to the human

remains.

| - - - - - -

THE

COASTS OF DEVON AND LUNDY ISLAND THEIR TOWNS, VILLAGES, SCENERY,

ANTIQUITIES AND LEGENDS - JOHN LLOYD WARDEN PAGE

AUTHOR OF 'AN EXPLORATION OF DARTMOOR AND ITS ANTIQUITIES, AN EXPLORATION

OF EXMOOR AND THE HILL COUNTRY OF WEST SOMERSET,' 'THE RIVERS OF DEVON, FROM

SOURCE TO SEA,' 'OKEHAMPTON: ITS CASTLE,' ETC., ETC.

WITH MAP AND ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON - HORACE COX - WINDSOR HOUSE, BREAM'S BUILDINGS, B.C.

1895

...

PART II. LUNDY ISLAND.

CHAPTER XIII. A GENERAL DESCRIPTION.

...

CHAPTER XIV. THE ISLAND KINGDOM.

...

Hubba Skeleton

A large area at the back of the farm is covered with outbuildings, not in the

best condition in fact, they look as

though they had been put up with a view to greater agricultural developments

than have as yet made their appear-

ance and then neglected.

They are all, as is the Manor House itself, of modern date some, indeed,

erected within the last few years.

It was while some of these " improvements" were in progress that

the workmen made a curious discovery.

While digging foundations for the wall of the rickyard, they came upon

a pair of kistvaens, or stone coffins, built of granite, and each covered with a

large slab.

The larger grave was loft, in length, and provided with a lump or pillow of

granite, hollowed out for the reception of

the head of a gigantic skeleton which lay within. The feet rested on another

block.

The smaller cist, which also contained a skeleton, was but 8ft. long, and

differed from the other in having no head or foot rest. Both were covered

with a pile of limpet shells.

Mr. Heaven was sent for, and the skeletons carefully measured.

The larger had a stature of 8ft. 2in.

Mr. Heaven was present the whole time, and not only saw the measurement taken,

but, as he himself told me, saw one of the men place the shin-bone of the

skeleton against his own, when it reached from his foot half-way up his thigh,

while the giant's jaw-bone covered not only his chin, but beard as well.

The skeleton in the smaller cist, although that of a very tall person, was

thought little of beside that of the giant.

Mr. Heaven, who has some knowledge of anatomy, considered it to be that of a

woman.

Close by seven other skeletons were discovered, but these were of ordinary

stature, and buried without stone coverings.

At the end of the line lay a great quantity of the bones of men, women, and

children, buried in one common grave.

Some glass and copper beads and one of gold were found with these bones, and

a few fragments of pottery. Some of these were preserved, and the bones were

then covered up.

As Mr. Chanter says, "it is most difficult to assign an era or to account

for this sepulture ; the remains of women and children precluding the idea of

its betokening the slain in battle, but rather the indiscriminate slaughter of

an entire population." Still, as he points out, this does not explain

the peculiar character and contents of the kistvaens.

These he refers to the Celtic period. But did the Celts produce such giants as

the pair interred in these stone coffins?

I fancy not.

Mr. Heaven exclaimed, when he saw the larger skeleton, " the

bones of Hubba the Dane

!"

and the proportions are certainly rather Scandinavian than Celtic.

Undoubtedly it was the custom of the Danes to remove their more honoured dead,

and Lundy was "the nearest point to which the defeated army and ships

could retreat."

...

Ubbe Ragnarsson - Ubbe, Ubba or Hubba Ragnarsson was a Norse leader during the Viking Age. Ubbe Ragnarsson was one of the sons of Ragnar Lodbrok and, along with his brothers Halfdan and Ivar the Boneless, a leader of the Great Danish Army. [1]

In 878, a party of Vikings landed on the English coast at Combwich. There they observed that a number of Saxons had taken refuge in the fort of Cynwit. The Vikings proceeded to besiege the fort, expecting the English to surrender eventually from lack of water. Instead of waiting to die of thirst on top of the hill, the Saxons attacked suddenly out of the fortress at dawn, taking the Danes by surprise and winning a great victory. Ubbe was killed by the Saxons under the leadership of Odda of Devon at the Battle of Cynuit in Somerset. The town of Hubberston in Pembrokeshire, South Wales was named for him.[2] Little is known about Ubbe Ragnarsson. The information that is available about him is written principally in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

Saxon

Hele Bay, Ilfracombe, north Devon

Saxon

Hele Bay, Ilfracombe, north Devon

When the Saxons were well established, in the winter of 878, early in the reign of King Alfred, Hubba the Dane attacked the north coast of Devon but was slain with over 800 men, and his standard, the Raven, was captured.

It has been variously suggested that this battle was at Kenwith Castle near Bideford; Wind Hill at Countisbury; Clovelly Dykes near Clovelly; Cannington Park in Somerset and Castle Hill near Beaford. A few years later there was another attack on a north Devon fort, usually thought to be Burridge hillfort, or possibly Ilfracombe, which had a Saxon defensive tower, now part of Holy Trinity Church. King Alfred may be remembered in the name Ilfracombe, thought to mean Alfred's valley, but it more likely remembers the name of a local lord.

The Danes never occupied north Devon, but certainly occupied Lundy (a Danish word meaning Puffin Island) and some graves found there probably date from the 9th century. One of them, called the Giants Grave, contained the skeleton of a man of unusual stature, some 8 2" tall and it was speculated that he was Hubba (5).

History of Northam village Devon

There are ancient records of Northam around the 10th/11th Century and also the story of the battle with Hubba the Dane at Bloody Corner in the late 9th Century. The tradition says he landed at, what is now Boathyde (Hyde being the word describing a Cove, the cove being behind the embankment), with a fleet of 33 ships and marched to attack the Hill Fort at Kenwith. Legend states that they were defeated by Odun, Earl of Devon, he and 1000 of his men were killed, the men being buried at Bonehill (Bunhill being the old name for a burying ground), and he being buried in a Cairn, in the area now known as Hubbastone.

There is a stone Tablet at Bloody Corner, in Northam, erected by

Charles Chappell, which says:-

Stop Stranger Stop,

Near this spot lies buried

King Hubba the Dane,

who was slayed in a bloody retreat,

by King Alfred the Great

So what really happened, and who really was involved will probably be never

known. There is also an area in The Copse, Northam Woods, which is

called King Alfreds Cave, and is reputed to be where King Alfred hid

when being chased by Vikings/Danes.

Bristol - Stanton Drew Stone Circle - This stone circle is not as famous as Stonehenge or Avebury, which is why there are a lot less tourists visiting it. This makes it a very atmospheric experience however, and with a little luck, you are the only one there. Except of course for the sheep grazing in the field. A definite recommendation if you are looking for an ancient site without the busloads of tourists.

Stanton Drew stone circles - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Stanton Drew - Stone Circles and Cove - Stanton Drew, Avon

Here we are interested in Hindringham

because of the early Utlage/Utlagh references:

Notice Bromholm is in Bacton and Bacton is only 15 miles from Runton/Beeston

Regis and 27 miles from Hindringham home of Robert de Utlagh is associated with

along with his son Alan Utlage.

I have also found a reference for

"Outlagh" in "Hindringham Outlagh Manor" An

essay towards a topographical history of the county of Norfolk - (no