|

[ Outlaw Genealogy | Bruce

History | Lost Chords ] [ Projects | News | FAQ | Suggestions | Search | HotLinks | Resources | Ufo ] |

|

[ Outlaw Genealogy | Bruce

History | Lost Chords ] [ Projects | News | FAQ | Suggestions | Search | HotLinks | Resources | Ufo ] |

The Navy of Edward VI and Mary I - C. S. Knighton

It is interesting that Thomas Spert was the Master of Trinity house till his death and we really don't know who replaced him afterward. It is interesting that he was the most experienced mariner Henry VIII had having gone to Newfoundland with Cabot. Here we see that his son did not take his place.

It seems a possibility that Adam Outlawe before his death may have been the Master of Trinity house sometime after the death of Spert in 1541 as he seems to be master of the Mary Rose in 1544 during the Expedition to Calais in France but died in the winter of 1544 . Adam Outlawe and family resided in the Tower Ward in 1541:

1541 - Adam Owtlawe - (£30) - '1541 London Subsidy roll: Tower Ward - "Lord Admiral" Sir John Dudley knight - William Gunston Navy Comptroller

Anyway , It was interesting learn

about how Spert had been with Cabot and the travels.

In 1497 Cabot leaves from Bristol for the new world and finds Newfoundland while

Henry VII rules.

Henry VII is not impressed and Cabot leaves England 1512, Cabot returns in 1516

after Henry VII's death and the beginning rule of Henry VIII. and returns to

Newfoundland with a young Thomas Spert , who becomes Master of Trinity House

(Mariners Guild) for life. ...

The Month - Early English Mariners

In referring to the early English seafarers, we shall have ,occasion to draw

largely from Mr. Fox Browne's two noteworthy volumes on English

Seamen under the Tudors, in which he has put together a quantity of

interesting records, not easy of access to all, in a bold and graphic narrative,

which might well have carried his readers through

another volume.

...

The Spanish expedition was conducted by Columbus, the English one by John

Cabot . It is a curious feeling to transport oneself in imagination to the

Bristol of those days—less smoky, dingy, and redolent of smells, let us hope,

than that of ours—the then nucleus of all the greatest merchants and most

enterprising traders of the time, and find there dwelling a grave-faced,

gold-spurred, Venetian knight, who had left his beautiful

birth-place to extend his trade. The tales of

Cathay, however, drew Cabot back to Venice, where he remained for fifteen years;

but, although all Europe—awakening to a fresh learning and civilisation, which

in the next century ripened into such marvellous fruits of good and evil—was

ringing with tales of wonder and adventure, Cabot reaped no encouragement on the

Continent, and was obliged to return to the little western island to carry out his

plans.

He sailed out of the Bristol Channel, in 1497, with his better-known son Sebastian, and, passing by Ireland, came to Labrador, which he called Newfoundland. Early one morning, just a year before Columbus left the West Indies, Cabot saw the mainland of America. St. John's Island was for a long time called the Island of Baccalaos, or codfish; and the discovery of these vast fisheries was the chief practical good of Cabot's expedition. But although he sailed in vain up and down the frowning and ice-bound coasts of Labrador, in search of the long-dreamt-of north-west passage to Cathay, and had to return bootless, his courage and endurance set the tide of adventure flowing in that direction, and thus, after a painful seed-time of disaster and death for many years, led to the colonisation of North America.

When Cabot returned to England, he was greeted with acclamations, and as, " clad in silk," he walked about London, crowds gathered after him, calling him the Great Admiral, and offering to serve under him wherever he chose to go. Henry VII. gave him all sorts of promises, and " money to amuse himself withal," though probably to a narrow extent, for the King's privy-purse shows this characteristic entry—"To hym that found the New Isle, ,£10." Three unfortunate Indians were afterwards brought to England, who were seen by Stow in Westminster Palace, as well as "hawks, wild cats, and popinjays," imported at a cost of 13s. 4d.

In fact,. Henry's avarice was so great that he allowed Cabot to languish twelve years in inactivity, till he became so disgusted that he went off, in 1512, to Spain, where he was received with open arms by King Ferdinand, who assigned him an allowance and a residence at Seville.

Ferdinand, however, soon afterwards died, and Cabot returned to England in

1516, whence he sailed to Newfoundland with Sir

Thomas Spert. The expedition was a failure, and, after one more

venture, Cabot again went to Spain, where he remained for thirty years ;

and going up the Parana and to Paraguay, he laid the foundations for the

Spanish possession of South America. He returned to England in 1548 (after Henry

VIII's death)

...

Henry VIII.'s reign was not marked by much adventure, but it was

signalised by a remarkable development of the navy. He built better and larger

ships, studied the causes of swift and slow sailing, and general navigation, and

much improved the sea stores and weapons. His plans

were admirably carried out by Cardinal Wolsey, and by Thomas,

Duke of Norfolk, who gave his two sons to

the service, and thus furnished two of the greatest English admirals ever known.

...

At last the upshot of all the preparations came out, and Sir

Edward's fleet of twenty-four ships was ready for sea, and for battle

with France. Henry VIII. went down to Greenwich to inspect it in person, and

made acquaintance with every one of the ships. The admiral's own flagship, of

600 tons, was the Mary Rose, and of her he wrote to the King—"She

is the noblest ship of sail, is this great ship, at this hour, that I trow be in

Christendom; the flower, I trow, of all ships that ever sailed." The

French had a fleet of fifty ships, augmented by some Mediterranean galleys,

commanded by the Knight of Rhodes, Jean le Bidoulx, called Prester John

by the English; but Sir Edward cared very little

how many ships there were. " Sir," he

wrote to the King, " God worketh in your cause and right. . . . The navy of

France shall do your Grace little hurt."

...

It was understood in those days that by virtue of the Pope's mandate and the

consent of nations, the countries discovered by Columbus should belong to Spain,

and to Spain only, so that, as yet, Englishmen held themselves aloof from

encroaching upon the rights of others, and sought other fields for their trade.

While Cabot was still absent, a great Bristol trader, Robert Thorne, fitted

out a few ships on his own account, and although

this venture and a second, more disastrous, under Hore, failed—as they both

sought the north-west passage, and were stopped by the ice and endless

hardships—still, enterprise was not the least daunted; and on Cabot's return

to England, a " Mystery and Company of Merchant Adventurers "

was organised, and a crowd of valiant and skilful captains, among whom were

William Burrows, Arthur Pet, Stephen Burrough, Sir Hugh

Willoughby, that " most valiant gentleman and well-born," and Richard

Chancellor—brought up in Sir Henry

Sidney's household—became noted in English annals. Sir

Henry Sidney himself, in a beautiful speech, recommended Chancellor to

the care of the " Mystery " merchants, in their first expedition,

which sailed past Greenwich Palace as Edward VI. lay on his

death-bed (1553). Poor Sir Hugh

Willoughby was separated from Chancellor in this expedition, and perished

miserably, with sixty men, on the Lapland coasts. Chancellor, more fortunate,

penetrated to the White Sea, and was invited to Moscow. This opened the

" Muscovy," or Russian fur-trade, to England, and the " Mystery

" came down to be the Muscovy Fur Company. Returning from his

second voyage from Russia, poor Chancellor also was drowned. The

patriarch of all these northern voyages did not long survive him, and to the

very end his heart was with the north-west

discoveries. We hear of Cabot last at the Christopher, at Gravesend, giving

liberal alms to the poor, that they might pray for Stephen Burrough's expedition,

whose departure was the object of the entertainment. Having " made great

cheer," the venerable old admiral " entered into the dance himself

with the young and lusty company, which being ended, he and his

friends departed, most quietly commending us to the governance of

Almighty God." Even on his death-bed the old

man rambled to Richard Eden about some revelation

made to him of an infallible way of finding the longitude ; and he departed very

peacefully at the age of eighty-five years, having lived through a complete era

of sea discoveries.

The chain of adventure was taken up in Elizabeth's reign by Anthony Jenkinson and Sir Humphrey Gilbert, the first of that knot of Devonshire " worthies " whose names have had a worldwide renown. Jenkinson's stay in Russia, as agent to the Muscovy Company, caused him to bring up the subject of Cathay again; and he wrote to Elizabeth, that if she would send an expedition thither, or to the " vast islands stored with gold, silver, and jewels near it"—probably he had heard of Japan—" she might make herself ' the famous princess of the world.'" But with all possible willingness to assert this character, Elizabeth had also too much of the true Tudor regard to the main chance to be dazzled by even golden birds in the bush. She preferred sending Jenkinson back to Russia, and Gilbert to Ireland, where he acquired a most unenviable reputation in the cruel work of butchery which the Queen was carrying on there against her Catholic subjects. But Gilbert's heart was in Cathay, and in 1574 he wrote his famous treatise on the way to it by the north-west passage. This treatise was lent from one person to another, and so revived the interest of all England on the subject, that Elizabeth sent Martin Frobisher to the Muscovy Company, to tell them that if they had given up trying to find the way to Cathay themselves, they had better hand over their privileges to some others, who would carry on the search. The chief adviser of the company at that time was Michael Lock, and he and Frobisher, and Sir Humphrey Gilbert, at last succeeded in organising a Cathay Company and several expeditions in search of the country. The chief noblemen of the Court, Lord Leicester, Lord Burghley, Sir Philip Sidney, and Walsingham, belonged to the company, and contributed to defray the expenses of the expedition, which Martin Frobisher was appointed to command; and when the first of his ventures sailed past Greenwich Palace, Elizabeth stood at the window and waved her hand, and then sent down to the shore to command Frobisher to come and take leave of her in person.

St. Martin,

Ludgate.

The ground is now the private garden of Stationers' Hall.

This church is the legendary burial place of Cadwallader and King Lud.

Churchyard more or less cleared 1894/5 and remains moved to Brookwood.

Christ Church, Newgate Street.

On the site of the Greyfriars monastery. The area of the burial ground was the nave of the friary church.

The burial place of many queens: The heart of Queen Eleanor of Provence, wife of Henry III (1291) Margaret, second queen of Edward I, (1318) Queen Isabella, wife of Edward II (d 1358) her daughter, Joan de la Tour, Queen of Scotland (1362)

. Also the burial place of Elizabeth Barton the Holy Maid of Kent (hanged at Tyburn

1534). This historic site is now a sanitised and dreary patch of grass.

On the site of the western end of the church of the Greyfriars. (Holmes)

Burial ground of the Black Friars

The Black Friars had a fairly extensive ground to the south of the Ludgate, in the area between Pilgrim street and Carter Lane. This was a popular place of burial for all classes (British History on line.) The church itself (sited just to the south of Carter Lane) was the burial place of many distinguished families. The ground and church disappeared after the Reformation.

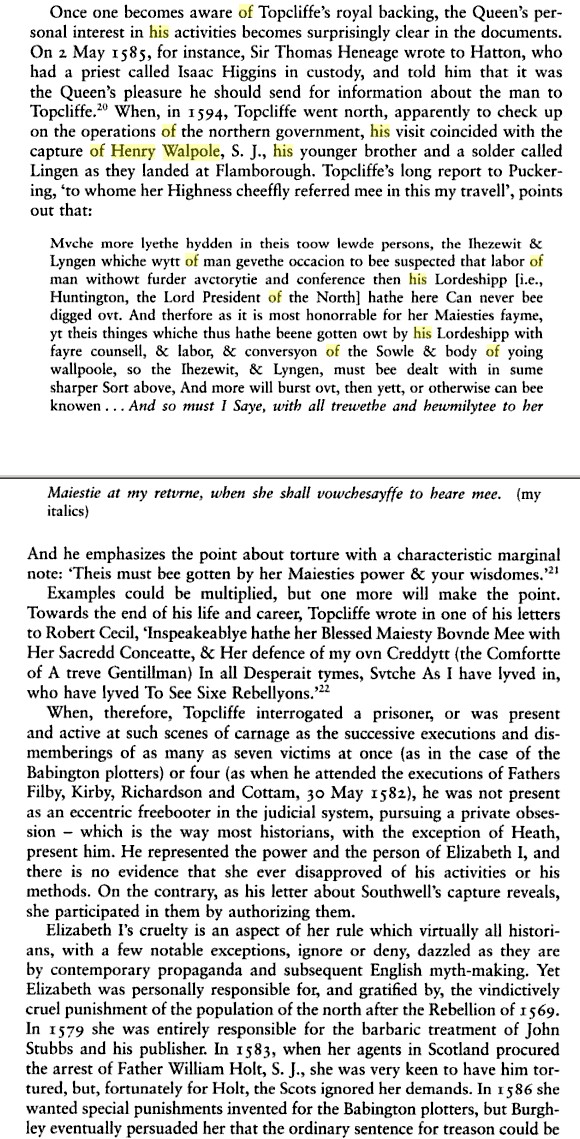

Found an interesting book about Henry Walpole (Norfolk family) also I am trying to track down statements he made in the presence of Richard Outlawe while in prison in York. This book does not mention Richard Outlawe but describes in detail the history of the times... this passage describes exactly what "hangings" were like under Elizabeth I and also where the term "let him Hang" comes from...There is also somewhere a record of discussions between Walpole and Outlaw

The Condition of Catholics Under James I.

The condition of Catholics under James I. - John Gerard

He was carried back to York, to be executed in the place where he was taken on his first landing in England, and while in prison there he had a discussion with some ministers which he wrote out with his own hand

Henry Walpole, S.J., was executed at York, April 7, 1595, for his Priesthood.

It was Father Walpole's custom to make notes of his conferences with ministers.

In the Public Record Office (_Domestic, Eliz._, vol. 248., n. 51) there is an interesting record in his own hand of his discussions while he was in the custody of Outlaw, the pursuivant.

Edmund Campion, S.J., suffered at Tyburn, Dec. 1, 1581, for a pretended conspiracy at Rome and Rhemes. The Act of 27 Elizabeth (1585), which made the mere presence of a Priest in England high treason, had not yet been passed.

This was said, of course, because it was dangerous to mention the names of any friends who were still at liberty. It could do no harm to mention those already in prison.

One generation of a Norfolk house a contribution to Elizabethan history

ONE GENERATION OF A NORFOLK HOUSE

...

98 THE JESUIT MISSION TO ENGLAND.

...

Meanwhile Campion had left London, and was wandering about the country,

handed from house to house by the agency of the Catholic Club, and carefully

watched over lest the pursuivants should come upon him unawares.

...

When, three weeks after this, he was put upon his trial, he had not sufficiently

recovered from the effects of his torture

to lift his hand at the bar. Of course he was condemned to die. On the 1st

December 1581 he was executed at Tyburn, little more than seventeen months after

he had landed at Dover.

Whoever will may read in Mr. Simpson's work the hideous details of that last

tragic scene, the dreary rainy morning, the motley procession, the dragging of

the wretched victims for there were three of them through the deep mire of the

London streets, the hanging and the cutting down, and the ghastly mutilation

that followed; the plunging of the executioner's knife into the quivering

bodies, the flinging of the bleeding members

into the cauldron that stood by, so that the blood was splashed into the

faces of the crowd that pressed round.

...

228 CAPTURE AND IMPRISONMENT

And so the horrible work went on. In 1587 three priests, in 1588 two,

in 1589 two more, suffered in this city of York alone for the crime of

saying mass or giving absolution, or simply setting foot on English soil.

Scarcely a year passed by with- out these dreadful massacres, the details of

which are more 5 revolting and shameful than those who have not given their

attention to the subject, or read the accounts written down at the time, could

be readily brought to believe. For ten years the butchery had been kept up

remorselessly.

The victims, as a rule, were not hung by the neck till" they were dead, but cut down while they were alive and conscious, then thrown upon their backs, the executioner's knife was plunged into their bowels, and the entrails and heart tossed into a cauldron of water which stood hard by. In more than one instance the victim in his agony and despair struggled with the hangman, but it was only for a moment. In some cases the crowd shouted out to the sheriff to " let him hang." Sometimes a condemned man begged as a special grace that he " might not be bowelled ere he were dead." The rabble looked on terror- struck, but such scenes could not but brutalise them. The 20 appetite for blood is a strange passion, and once yielded to is prone to exercise a horrible fascination on some minds.

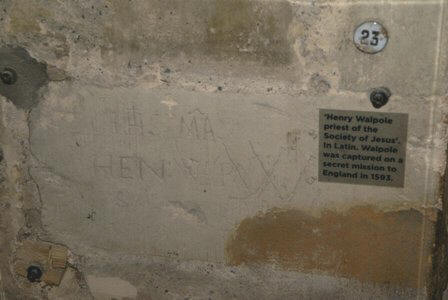

Tower of London - The Salt Tower: Built in 1240, it held prisoners during Tudor times, including English Jesuit priest Henry Walpole...

... who left some graffiti

on the walls.

... who left some graffiti

on the walls.

St.

Edmund Campion is celebrated for his defense of conscience as martyr of the

Catholic Church. Another Englishman, Henry Walpole, was transformed as he

witnessed Campions bloody death. - An inscription

left by St. Henry Walpole in his English prison cell in 1595

St.

Edmund Campion is celebrated for his defense of conscience as martyr of the

Catholic Church. Another Englishman, Henry Walpole, was transformed as he

witnessed Campions bloody death. - An inscription

left by St. Henry Walpole in his English prison cell in 1595

WALPOLE, HENRY (1558–1595), jesuit, eldest son of Christopher Walpole of Docking and of Anmer Hall, Norfolk, by Margery, daughter and heiress of Richard Beckham of Narford in the same county, was born at Docking, and baptised there in October 1558. Michael Walpole [q. v.] and Richard Walpole [q. v.] were his younger brothers. Henry was sent to Norwich school in 1566 or 1567, where his master was Stephen Limbert, a Cambridge scholar of some repute in his day. He entered at St. Peter's College, Cambridge, on 15 Jan. 1575, but he left the university without taking a degree, and in 1578 he became a student at Gray's Inn, intending to follow in the footsteps of his father, who appears for some time to have practised as a consulting barrister, and of his uncle, John Walpole, a serjeant-at-law who would certainly have been promoted to a judgeship but for his early death in 1568. While Henry Walpole was at Gray's Inn he appears to have brought himself under the notice of the government spies by habitually consorting with the recusant gentry and the Roman partisans; and when Edmund Campion [q. v.] came over to advocate a return to the papal obedience, Walpole was a conspicuous supporter of the jesuit and his friends.

Campion was hanged at Tyburn on 1 Dec. 1581, and Walpole stood near to the scaffold when the usual barbarities were perpetrated upon the mangled corpse. The blood splashed into the faces of the crowd that pressed round, and some of it spurted upon young Walpole's clothes. He accepted this as a call to himself to take up the work which Campion had begun; and under the inspiration which the dreadful scene had aroused he sought relief for this feeling in writing a poem of thirty stanzas, which he entitled ‘An Epitaph of the Life and Death of the most famous Clerk and virtuous Priest, Edmund Campion, a Reverend Father of the meek Society of the blessed name of Jesus.’ The poem, which contains many passages of much beauty and sweetness, and indicates the possession of great poetic gifts on the part of the writer, was immediately printed by one of the author's friends, Valenger by name, apparently at his own private press. It was widely circulated, and attracted much attention. The government made great efforts to discover the author. Valenger was brought before the council, was fined heavily, and condemned to lose his ears; but he did not betray his friend. Walpole, however, was under grave suspicion, and thought it advisable to slip away to his father's house in Norfolk, where he was for some time in hiding, till an opportunity came for passing over to the continent. He arrived at Rheims on 7 July 1582, and at the college there he enrolled himself as a student of theology. Next year he made his way to Rome, was received into the English College on 28 April 1583, and in the following October was admitted to minor orders. Three months later he offered himself to the Society of Jesus, and on 2 Feb. 1584 was admitted among the probationers. A year later he was sent to France, where, at Verdun, he passed two years of probation, acting as ‘prefect of the convictors.’ On 17 Dec. 1588 he was admitted to priest's orders at Paris.

About 1586 a staff of army chaplains had been organised by Belgian jesuits, whose business it was to minister to the Spanish forces serving under the prince of Parma. Among these were soldiers of almost every European nationality, and it was important that the jesuit chaplains should be good linguists. Walpole was master of many languages, and was exactly the man for this work, which was now laid upon him. He was eminently successful, and he did not spare himself; but on one occasion in the autumn of 1589 he fell into the hands of the English garrison at Flushing, and was thrown into prison among common thieves and cut-throats, and had to endure great sufferings, till his brother, Michael Walpole, managed to cross over to Flushing and pay the ransom demanded for his release. In January 1590 he was set free and was still in Belgium, apparently exercising his functions as a catholic priest among the soldiery, when in October 1591 he was removed to Tournai to complete his third year as probationer.

In July 1592 he was summoned to the jesuit college at Bruges. Parsons's famous ‘Responsio ad Edictum,’ written under the name of Philopater [see Parsons, Robert, (1546–1610)], was published in the summer of 1592, and it was deemed advisable that an English translation of the book should be circulated coincidently with the appearance of the Latin version. This translation was entrusted to Walpole, and while he was engaged upon it he received orders from Claudius Aquaviva, general of the society, to join Parsons in Spain. He was present at the opening of the chapel of the lately founded jesuit college in Seville on 29 Dec. 1592, and there he met his brother Richard, whom he had not seen for ten years. Richard had already volunteered to engage in the English mission, but Parsons could not spare so able a coadjutor, and Richard had to wait his time. Henry, however, was possessed by the longing to return to England and emulate John Gerard's success as a proselytiser in Norfolk [see Gerard, John, (1564–1637)].

In June 1593 Parsons told him that it was decided he should be sent to England. Next month he was presented to Philip II at the Escurial, and was very graciously received as a jesuit father about to start on the English mission. It was not, however, till late in November that he actually set sail from Dunkirk on one of the semi-piratical vessels which at that time infested the Channel, having bargained that he should be put ashore on the coast of Essex, Suffolk, or Norfolk, where he was sure to find friends or kinsfolk. With him went two soldiers of fortune who had been serving under the king of Spain and were tired of it. One of these was Thomas, a younger brother of Henry Walpole, now in his twenty-sixth year. The voyage was disastrous from the first; the wind was boisterous and adverse, the vessel could not touch at any point near the East-Anglian coast, and was unable to stand inshore till they had got as far as Bridlington in Yorkshire, where at last the three travellers were landed on 6 Dec. and left to shift for themselves. The little party had scarcely been twenty-four hours on English soil before they were all arrested and committed to the castle at York.

Henry Walpole at once confessed himself a jesuit father. The other two allowed that they had served in Sir William Stanley's regiment in Flanders. This, it seems, was no offence in law, and the only charge which could be made against them was that they had connived at the landing of a jesuit in England, which was a much more serious matter. The two made no difficulty of telling all they knew. Thomas Walpole even pointed out the place where his brother had hidden some letters and other incriminating documents on his first landing. But Henry exhibited unusual stubbornness when under examination, and, following the example of his hero Campion twelve years before, declared himself ready to defend his religious convictions against a member of the Yorkshire clergy in a public discussion, in which he acquitted himself with only too great success and cleverness. In February he was committed to the care of the notorious Richard Topcliffe [q. v.], under whose charge he was carried to London and placed a close prisoner in the Tower.

It was not till 27 April that he was subjected to his first examination upon the information which the government had been collecting against him. This was a preliminary to a long succession of similar attempts to extort from the prisoner particulars which it was supposed he only was qualified to furnish on the movements of the catholics abroad and the plots which were assumed to be hatching at home. Minute reports of these examinations were drawn up at the time which have come down to us. Walpole was put upon the rack again and again, and Topcliffe seems to have used his utmost license in torturing his victim.

In July 1594 he was still able to write, but after this he was handed over to Topcliffe to treat as he pleased. There is some reason for thinking that there was a motive for keeping him alive. Henry Walpole was his father's eldest son and heir. His father was at this time in failing health, and in the event of his son surviving him a considerable estate would have escheated to the crown.

In the spring of 1595, however, he was sent back to York for trial on the capital charges: (1) that he had abjured the realm without license; (2) that he had received holy orders beyond the seas; and (3) that he had returned to England as a jesuit father and priest of the Roman church to exercise his priestly functions. Of course he was found guilty, though during the trial he acquitted himself with great ability, and he was condemned to death. The sentence was carried out on 17 April 1595. The long and minute accounts which have reached us of his conduct during the last few days of his life prove the great interest that was felt in his case, and though the judicial murder of Henry Walpole and of Robert Southwell [q. v.] by no means brought to an end the massacre of the jesuits and seminary priests in the queen's reign, yet after this year (1595) the rack was much more sparingly used than heretofore, and something like hesitation was shown in sending the Roman proselytisers to the gallows.

A portrait of Henry Walpole, stated to be contemporary, was preserved in the English College at Rome till the general spoliation of the religious houses. A copy of this was made for the late Hon. Frederick Walpole of Mannington Hall, Norfolk. A collection of nineteen ‘Letters of Henry Walpole, S. J., from the original manuscripts at Stonyhurst College, edited with notes by Aug. Jessopp, D.D.,’ was printed for private circulation in 1873, 4to. Only fifty copies were struck off. Twenty-five of these were presented to the fathers at Stonyhurst.

[The career of Henry Walpole has been traced in detail by the writer of this article in ‘One Generation of a Norfolk House,’ 1878. The authorities on which the statements there made are based will be found in the notes. A short life of Henry Walpole was published by Father Cresswell at Madrid eight months after the execution of his friend. A French translation of this Spanish original was issued at Arras in September 1596, and it has been asserted that an English version was also printed. This, however, is very doubtful. There is a full account of Walpole's career, with some of his letters and details of his trial, in Diego de Yepes's Historia Particular de la Persecucion de Inglaterra, published in quarto at Madrid in 1599 (only four years after Walpole's death), and in our own times much valuable information has been brought together in Foley's Records of the English Province S. J.; Morris's Life of John Gerard; and in the Records of the English Catholics under the Penal Laws, edited by the London Oratorians, 1878, vol. i. The Official Reports of Walpole's examinations in the Tower are abstracted in Cal. Dom. Eliz. 1591–4; the originals are in the Record Office. The reports of the disputations at York, of the trial, and of the incidents at the execution must have been widely circulated. We find them quoted in unexpected places. Of course they were known to More (Hist. Prov. Angl.), but one is surprised to find extracts from them in the Kerkelyke Historie of Corn. Hazart S. J., folio, Antwerp, 1668, iii. 375. A devotional life of Henry Walpole, taken almost exclusively from Cresswell's biography, was published by Father Alexis Possoz, S. J., at Tournai in 1869.]Here we see Richard Outlawe is EARL OF HUNTINGDON's , the president's pursuivant

Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon

Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon

His father died on 25 January 1560 and Henry became the third Earl of Huntingdon. At the time few members of the Tudor dynasty remained alive and several descendants of the previous English royal house of Plantagenet were seen as possible heirs to the throne. Huntingdon was among these possible heirs and won a certain amount of support, especially from the Protestants and the enemies of another claimant Mary, Queen of Scots. However, Elizabeth now had reasons to distrust him and as a result several honours were kept out of his reach.

However, he was still useful to her. He was named a Knight of the Garter in 1570, alongside William Somerset, 3rd Earl of Worcester. In 1572 he was appointed president of the Council of the North, and during the troubled period between the flight of Mary, Queen of Scots, to England in 1568 and the defeat of the Spanish Armada twenty years later he was frequently employed in the north of England. It was doubtless felt that the earl's own title to the crown was a pledge that he would show scant sympathy with the advocates of Mary's claim. He assisted George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury, to remove the Scottish queen from Wingfield Manor to Tutbury, and for a short time in 1569 he was one of her custodians. He was later one of the Peers at her trial in 1586.

Huntingdon was responsible for the compilation of an elaborate history of the Hastings family, a manuscript copy of which is now in the British Museum. Having died without heir his earldom passed to his brother, George.

EARL OF HUNTINGDON LORD PRESIDENT OF THE NORTH

...

What should I speak of Richard Outlaw, Collier, Robson, Sanderson, Spain, Rollinson, Bannister, Scarcroft, and a great number more, of no better disposition than the former, whose lives, practices, and behaviours are [so] notorious, that, if I should write all I hear reported by the mouths of credible persons, I should easily fill a book with tragical discourses of their infamous actions? This I have already said may suffice to give some aim what disposition the rest are of, and what kind of men they be, that now-a-days are desired, chosen, and employed for principal instruments and actors of this present persecution; who being of their own nature and vicious inclination prone to exercise cruelty, you may easily conjecture what mischief they are like to practise against catholic men, to whose oppression they are destinate principally, if their proceeding be not only to the shew justified with pretence of law, but also confirmed and warranted by special authority, and particular commissions, directed and given unto them; the which they always interpret in such ample sense, and execute with such rigour, that the only name of their commission serveth them to justify all actions and injuries committed by them, where the words and construction of their commissions doth by no means insinuate any license to approve many voluntary attempts. And because, after the wise man's experience, "we have seen under the sun, in the place of judgment, wickedness, and in the place of justice, iniquity,"1 let us first consider the authority of the president and other chief officers, with the use or abuse thereof, and from them descend unto their inferior vassals.

The president in this north country hath had, and hath yet, as he taketh upon him, three several and principal authorities granted unto him, of president, of lieutenant, and also of a head commissioner, next after the supposed archbishop of

York, who is the foremost and first of that commission.

...

The president, therefore, having missed his purpose, was much disquieted in mind, and all melancholy, and, not finding which way better to satisfy his fury (although he offered money to those that could betray the man he sought for), determined with himself to disperse the prisoners of the castle into other places, where they should be kept under a more strait custody, lest they should, at any time, through the negligence of their keepers, obtain or devise the means to receive comfort, by access of their pastors, as he suspected they had done before.

Wherefore, not long after, he sent seventeen of the principal unto Hull, whereof nine were committed unto

Henry Hubbart, the keeper of the north Blockhouse, and the rest to Beesely, keeper of the

Castle, which two prisons were wont to be the worst places, for extremity shewed, in all this north country.

Upon Easter Tuesday following, he caused another search to be made, at a gentlewoman's house in Nidderdale, called Mrs. Ardington; for it had been certified him by his espials, that Mr. David Ingleby (the gentlewoman's brother, and one whom the president loveth not, being a catholic) and the lady Anne Nevill were there. Wherefore [he] sent with all speed a company of bad companions of his own household, for more trust and assurance, amongst whom, by name, were Pollard, gaoler of Sheriffhutton, Outlaw, the president's pursuivant, and a gaoler also, with one Eglesfield, a traitor, of whom you shall hear more afterwards.

In their way, they forced a poor man out of his house, Jo be their guide; and, coming near the house, they drew their swords, bent their pistols, and buckled themselves for battle, as though they would have made an assault to the gentlewoman's house : but perceiving, by one of the house, that there was no fear of fighting, the greatest resistance consisting only in a company of women, they put up their weapons, entered in, the door being open, searched, rifled, turned and tossed all things upside down, but found nothing greatly for their purpose. Yet, fearing to be disappointed of their journey, they determined not to depart with speed, but seated themselves in the house, and, as though all were their own, made provision for themselves, at the gentlewoman's cost, until Thursday or Friday following: during which time they kept the house, they found in the house certain apparel of some gentleman, as doublets, hose, silk and Guernsey stockings. Upon them they seized by the president's warrant, whose beggary is such, that he is not otherways wont to reward his trusty servants, than with the spoils of such as he persecuted. Yet the pursuivant returned home all in a chafe, that he sped no better; and his wife also not well appaied that his budget came so light home; for she was accustomed always to give the first welcome unto his capcase, at his return home, which seldom or never before came so empty

List of Presidents of the Council of the North

Theatre and religion Lancastrian Shakespeare - Richard Dutton, Alison Findlay, Richard Wilson

Gee I wonder.why...

William Allen (cardinal) - (1532 – 16 October 1594) was an English Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church. Allen helped plan the Spanish Armada's invasion of England, and was to have been Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor had it succeeded. The Douai Bible was printed under Allen's direction. His activities were part of the Counter Reformation, but made matters worse for Roman Catholics in England. He influenced Pope Pius V to depose Elizabeth I. After the Bill of Deposition was issued, Elizabeth chose not to continue her policy of religious tolerance and instead began the persecution of her religious opponents.

Bashing Secularism 40 Martyr Reflections Saint Henry Walpole

Fr Walpole was hanged, dismembered, disemboweled and quartered for all to

see. His arms, legs and genitals were cut off and committed to the flames.

Finally, he was beheaded. Fr Walpole's death was said to be a great boost

for Catholicism in the north. The Earl of Huntingdon,

known as a great persecutor of northern papists, died shortly afterwards -

apparently in great remorse.

Who were these people and what was the beef?

1568-69 - Payne

v Saunders, Nicholson, Mitchell, Owtlawe.

- Court of Star Chamber: Proceedings, Elizabeth I plaintiffs

1578-79 - Woodhouse v. Outlawe - Court of Star Chamber: Proceedings, Elizabeth I - 21 Eliz -

Also - So why two entries with different spellings? :

1578-79 - Woodhouse

v. Owtelawe - Court

of Star Chamber: Proceedings, Elizabeth I - 21 Eliz

Also - So who was Bate ? :

1578-79 - Woodhouse

v. Bate and Owtlawe - Court of Star Chamber - 21 Eliz

BBC - History - Historic Figures

Mary, Queen of Scots (1542 - 1587)

...

This turned the Scottish nobility against Mary. Bothwell was exiled and Mary

forced to abdicate in July 1567. In 1568, her supporters were defeated in

battle and she fled to England seeking refuge from her cousin, Elizabeth I. Mary

had a strong claim to the English throne and therefore posed a threat to

Elizabeth, who had her imprisoned.

What was the religion of Queen Elizabeth I

... when Mary Queen of Scots, a devout Catholic and claimant to the

English throne, arrived in England in 1568 Catholic dissention quickly broke

out. Countless plots to overthrow Elizabeth and seat Mary were schemed. Mary

was eventually executed for her involvement in the conspiracies in 1587.

On 2 May 1568, Mary escaped from Loch Leven with the aid of George Douglas, brother of Sir William Douglas, the castle's owner.[136] She managed to raise an army of 6000 men, and met Moray's smaller forces at the Battle of Langside on 13 May.[137] She was defeated and fled south; after spending the night at Dundrennan Abbey, she crossed the Solway Firth into England by fishing boat on 16 May.[138] She landed at Workington in Cumberland in the north of England and stayed overnight at Workington Hall.[139] On 18 May, she was taken into protective custody at Carlisle Castle by local officials.[140]

Mary apparently expected Elizabeth to help her regain her throne. Elizabeth was cautious, and ordered an inquiry into the conduct of the confederate lords and the question of whether Mary was guilty of the murder of Darnley. Mary was moved by the English authorities to Bolton Castle in mid-July 1568, because it was further from the Scottish border but not too close to London. A commission of inquiry, or conference as it was known, was held in York and later Westminster between October 1568 and January 15

Some interesting reference books:

The progresses and public processions of Queen Elizabeth Volume I - John Nichols

1600 - The Queen honoured the nuptials of Lord Herbert with her presence in Black Friars

The progresses and public processions of Queen Elizabeth Volume II - John Nichols

The progresses and public processions of Queen Elizabeth Volume III - John Nichols

From page 2: we have more about the Blackfriars connection...

So who was this prominent Henry Outlawe Gentleman in London who was involved with the Blackfriars Playhouse in the early 1600's??? Did he know Shakespeare?

1603/4-1609 - Henry Outlawe deposes on Edward Kirkham's behalf that for a total of fifteen weeks between 1603 and 1604, Henry Evans collected 30s a week 'for the use of stools standing upon the stage at Blackfriars.' Outlawe does not believe that Evans gave account of this income to the rest of the sharers. - Blackfriars - St Anne's - London - English professional theatre, 1530-1660

Interesting - Blackfriars was first given to Sir Francis Bryan (who knew mariner Adam Owtlawe) by King Edward VI :

All the year round a weekly journal - Charles Dickens

King Edward the First and Queen Eleanor heaped many gifts on the sable friars. Charles the Fifth was lodged at their monastery when he visited England, and his nobles resided in Henry's new-built palace of Bridewell, a gallery being thrown over the Fleet and driven through the City wall to serve as a communication between the two mansions. Henry held the "Black Parliament" in this monastery, and hero Cardinal Campeggio presided at the trial which ended with the tyrant's divorce from the ill-used Katherine of Arragon. In the same house the parliament also sat that condemned Wolsey, and sent him to beg "a little earth for charity" of the monks of Leicester.The rapacious king laid his rough hand on the treasures of the house in 1538, and Edward the Sixth sold the Hall and Prior's Lodgings to Sir Francis Bryan, a courtier, afterwards granting Sir Francis Cawarden, master of the revels, the whole house and precincts of the Preacher Friars, the yearly value being then reckened at nineteen pounds. The holy brothers were dispersed to beg or thieve, and the church was pulled down, but the mischievous right of sanctuary continued.

And now we come to the event that connects the old monastic ground with the name of the great genius of England.

James Burbage, Shakespeare's friend and fellow-actor, and other servants of the Earl of Leicester, tormented out of the City by the angry edicts of over-scrupulous lord mayors, took shelter in the precinct, and there, in 1578, erected a play-house (Playhouse-yard).

Every attempt was in vain made to crush the intruders.

About the year 1586, according to the best authorities, the young Shakespeare came to London and joined the company at the Blackfriars Theatre.

Only three years later we find the new arrival (and this is one of the nnsolvable mysteries of Shakespeare's life) one of sixteen sharers in the prosperous though persecuted theatre. It is true that Mr. flalliwell has lately discovered that he was not exactly a proprietor, but only an actor receiving a share of the profits of the house, exclusive of the galleries (the boxes and dress circle of those days), but this is after all only a lessening of the difficulty, and it is almost as remarkable that a young unknown Warwickshire poet should receive such profits, as it is that he should have held a sixteenth of the whole property. Without the generous patronage of some such patron as the Earl of Southampton or Lord Brooke, how could the young actor have moved? He was twenty-six, and may have written Venus and Adonis or Lucrece, yet the first of these poems was not published till 1593. He may have already adapted one or two tolerably successful historical plays, and, as Mr. Collier thinks, might have written the Comedy of Errors, Love's Labour Lost, or the Two Gentlemen of Verona. One thing is certain, that in 1587 five companies of players, includingthe Blackfriars company, performed at Stratford, and in his native town Mr. Collier thinks Shakespeare first proved himself useful to his new comrades.

In 1589 the lord mayor closed two theatres for ridiculing the Puritans. Burbage and his friends, alarmed at this, petitioned the privy council, and pleaded that they had never introduced into their plays matters of state or religion. The Blackfriars company, in 1593, began to build n summer theatre, the Globe, in Southwark; and Mr. Collier, remembering that this was the very year Venus and Adonis was published, attributes some great gift of the earl to Shakespeare to have immediately followed this poem, which was dedicated to Southampton. That money may have gone to build the Globe.

By 1594, the poet had written Richard the Second and Richard the Third, and must have been recognised as a great writer.

In 1596, we find Shakespeare and his partners (only eight now) petitioning the privy council to allow them to repair and enlarge their theatre, which the Puritans of Blackfriars wanted to close. The council allowed the repairs, but forbade the enlargement. At this time Shakespeare was living near the Bear Garden, Southwark, to be close to the Globe. He was now evidently a thriving, "warm" man, for, in 1597, he bought for sixty pounds New Place, one of the best houses in Stratford.

In 1613, we find Shakespeare purchasing a plot of ground not far from Blackfriars Theatre, and abutting upon a street leading down to Puddle Wharf, "right against the king's majesty's wardrobe;" but he had retired to Stratford, and given up London and the stage before this. The deed of this sale was sold in 1841 for one hundred and sixty-two pounds five shillings.

Charles Dickens, Jan.] CHRONICLES OF LONDON STREETS. [November 4,1871.] 543

In 1608, the lord mayor and aldermen of London made a final attempt to crush the Blackfriars players, but failing to prove to the Lord Chancellor that the City had ever exercised any authority within the precinct and liberty of Blackfriars, their cause fell to the ground. The corporation then opened a negotiation for purchase with' Burbage, Shakespeare, and the other (now nine) shareholders. The players asked about seven thousand pounds, Shakespeare's four shares being valued at one thousand four hundred and thirty-three pounds six shillings and eight pence, including the wardrobe and properties, estimated at five hundred pounds. His income at this time Mr. Collier estimates at four hundred a year. The Blackfriars Theatre was pulled down in Cromwell's time, 1655, and houses built in its room.

| - - - - - -

Shakespeare’s property in Blackfriars

Val Hart, Assistant Librarian at Guildhall Library, unravels the history behind the Shakespeare deed, one of the City of London’s greatest treasures, which bears one of only six authenticated examples of Shakespeare’s signature.

I

Gyve . . . unto my Daughter Susanna Hall . . . All that Messuage or

ten[emen]te with th' appurtenances wherein one John Robinson dwelleth, scituat,

lyeing & being in the blackfriars in London nere the Wardrobe. With these

words William Shakespeare of Stratford upon Avon, gentleman, bequeathed to his

descendants the only property he is known to have owned in London. Why he

purchased it is not known. He may have intended to live there – it was

conveniently situated for both the Blackfriars Theatre and the Globe Theatre

just across the river – but there is no evidence to suggest that he ever did

so. It is more likely that he bought it as an investment or to enhance his

status as a gentleman.

Since 1843, when it was bought at auction by the Corporation of London for £145, the title deed to Shakespeare’s Blackfriars property has been one of the City’s greatest treasures. Although it is the vendor’s, not the purchaser’s copy – Shakespeare’s copy is in the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington – the deed bears one of only six “authenticated” examples of Shakespeare’s signature.

The deed describes the property purchased in some detail:

All that dwelling house or Tenement with th’appurtenaunces situate and being within the Precinct, circuit and compasse of the late black Fryers London, sometymes in the tenure of James Gardyner Esquiour, and since that in the tenure of John Fortescue gent, and now or late being in the tenure or occupacion of one William Ireland or of his assignee or assignes; abutting upon a streete leading downe to Pudle wharffe on the east part, right against the Kinges Maiesties Wardrobe; part of which said Tenement is erected over a great gate leading to a capitall Messuage which sometyme was in the tenure of William Blackwell Esquiour deceased, and since that in the tenure or occupacion of the right Honorable Henry now Earle of Northumberland; And also all that plott of ground on the west side of the same Tenement which was lately inclosed with boordes on two sides thereof by Anne Bacon widowe, soe farre and in such sorte as the same was inclosed by the said Anne Bacon, and not otherwise, and being on the third side inclosed with an olde Brick wall; Which said plott of ground was sometyme parcell and taken out of a great peece of voide ground lately used for a garden.

The deed of purchase is dated 10 March 1613 and was made between the vendor, Henry Walker, Citizen and Minstrel of London on the one part, and William Shakespeare, William Johnson, Citizen and Vintner of London and John Jackson and John Hemmyng, both described as gentlemen of London, on the other part. Shakespeare was the sole purchaser; the men named with him acted as trustees. It is tempting to equate Johnson with the landlord of the Mermaid Tavern in Cheapside and Hemmyng with John Heminges, actor, manager and editor of the Shakespeare first folio, but the identity of John Jackson remains uncertain.

On the following day (11 March 1613) Shakespeare executed another deed stipulating that £60 of the purchase price was to remain on mortgage until paid in whole the following September. Whether this sum was ever paid is not known.

After

the dissolution of the Blackfriars monastery in 1538, its land and buildings had

been parcelled out to ambitious courtiers. The estate of which

Shakespeare’s property formed part was granted in 1547 to Sir Francis Bryan,

dubbed “The Vicar of Hell” by Thomas Cromwell.

After Bryan’s death in 1550 it came into the hands of Thomas Thirlby, Bishop of Norwich, later Bishop of Ely, who then sold it to William Blackwell, Common Clerk of the City of London.

In 1590 the estate was divided between two of William’s children, William Blackwell junior and Anne Bacon. Anne’s portion contained the gatehouse property, and in 1604 her son Mathie (also called Matthew or Mathias) Bacon, sold this part of the estate to Henry Walker for £100. Later the same year Walker leased the gatehouse to William Ireland, Citizen and Haberdasher of London, for 25 years.

The exact date at which Shakespeare’s property passed out of the hands of his descendants is not known, but in August 1667, Edward Bagley, a kinsman of Shakespeare’s grand-daughter, Elizabeth Barnard, sold the site to Sir Heneage Fetherston. As the Blackfriars area had been razed to the ground by the Great Fire of the previous year, Bagley received only £35 for the land.

Despite the detailed description in the deed it has proved difficult to locate the exact site of Shakespeare’s property. We know that it abutted on the street leading down to Puddle Wharf which is now St Andrew’s Hill. The Wardrobe which it was near or “right against,” is commemorated in Wardrobe Place. However, even the Shakespearean scholar James O. Halliwell-Phillipps, who owned an abstract of title to Fetherston properties in Blackfriars (now in the Folger), could arrive at no firmer conclusion than that the gatehouse property stood either partially on or very near Ireland Yard. The present day passage of this name, which runs west out of St Andrew’s Hill, undoubtedly derives its name from the Ireland family who owned or occupied property in the Blackfriars area at least as early as 1582. Deeds, plans and the Folger abstract of title suggest that Shakespeare’s property may have occupied the north side of Ireland Yard where it joins St Andrew’s Hill, but this is still research in progress.

Interesting connection of the earlier Thomas Outlaw and an early mention of the Burbage family and William Martyn the Mayor of London::

1492 - Thomas

Outlawe - 1 acre with a garden on the

southern boundary in Mattishall, the south head of which abutted onto the

King's highway

1493 - Inquisition

taken at the Guildhall - London, 23 March, 8 Henry VII [1493], before William

Martyn, Mayor and escheator, after the death of Edward Greene, by the

oath of John Machyn, Thomas Outlawe, John Gage, Thomas Couper, William

Wodestok, Henry Calvar, Thomas Rayner, Thomas Lybbys, Nicholas Jefray, William

Cambre, Richard Spycer, John Broune, John Knyght, Thomas Chamberleyn, and

Richard William - GUILDHALL

London - Guildhall,

London

Inquisition taken at the Guildhall, 23 March, 8 Henry VII [1493], before William Martyn, Mayor and escheator, after the death of Edward Greene, by the oath of John Machyn, Thomas Outlawe, John Gage, Thomas Couper, William Wodestok, Henry Calvar, Thomas Rayner, Thomas Lybbys, Nicholas Jefray, William Cambre, Richard Spycer, John Broune, John Knyght, Thomas Chamberleyn, and Richard William, who say that

Cecilia, who was the wife of Robert Grene, knight, and late the wife of John

Acton, was seised of a tenement called the Bell, situate in the parish of the Blessed Mary de Arcubus, which was late the property of the said Robert Grene, who held it in free burgage: it is worth perann., clear, £6.

Elizabeth Grene, late the wife of Walter Grene, esq., John Pemberton, clerk, John Gayesford,

John Catesby, and John Ardern were seised of a tenement situate in the parish of St. Thomas the Apostle in the ward of Vintrie, and so seised they demised the said tenement to John Doune, senior, citizen and mercer of London, for the term of 20 years from Michaelmas, 38 Henry VI [1460], at the yearly rent, for the 2 first years of the said term, of 5 marks, and for the other 18 years 10 marks. Afterwards, the said Elizabeth, John Pemberton, John Gaynesford, and John Ardern died, and

John Catesby was alone seised of the said tenement: he had issue Humphrey

Catesby, who after his father's death entered into the same tenement as his son and heir.

The said tenement is held in free burgage, and is worth per ann., clear, £4.

No other lands came into the hands of the King by the death of the said Cecilia, neither on account of the minority of Edward Grene, her son and heir.

Edward Grene died 14 January last past; Cecilia, now the wife of William

Burbage, is his sister and heir, and is aged 26 years and more. Inq. p. m., 8 Hen. VII, No.

21.

1493 - Death of Ellen Wodeward witnessed by Thomas Outlawe - London - 23 March, 8 Henry VII

1497 - Death of Richard Chamberleyn witnessed by Thomas Outlawe - London - 4 March, 12 Henry VII - 1497

1504-5 - In

the tyme of Laurence Aslyn mr willm pecok and Thomas Outlawe wardeyns

- History of the Pewterers' Company - glasid by Thomas Owtlawe pg

74, pg 76

| - - - -

William Martyn was pretty interesting and his home still exists:

William Martyn - of Athelhampton, near Dorchester, Dorset (c. 1446 – 14 January 1503).

Sir William Martyn, Sheriff of London in 1484 and Lord Mayor of London in 1492, built the current Great Hall of Athelhampton in or around 1485. He also received licence to enclose 160 acres (647,000 m²) of deer park and to fortify his manor. Effigies of him and his family can be seen in the Church of Saint Mary in nearby Puddletown.

Athelhampton House and Gardens

Backing onto the River Piddle and surrounded by lovely gardens, Athelhampton is one of the finest houses of its period. Begun in 1485 by Sir William Martyn, a prosperous London merchant who later became Lord Mayor, the house has a beautiful facade of warm limestone, with rows of mullioned windows and an oriel. Inside you can tour many of the rooms, including the Great Hall which is at the heart of the house.

The house remained in the Martyn family for the next 4 generations,

but in 1891 it was purchased by Alfred Cart de Lafontaine, who set about

restoring the house and creating the formal gardens that can be seen today.

The house is currently run by the grandson of Robert Victor Cooke who purchased

the house in 1957.

Athelhampton is reputedly one of the most haunted buildings in Dorset,

with a pair of duellists, the Grey Lady and a pet ape apparently being amongst

its ghostly occupants! All was quiet on the day we visited we're glad to

say!

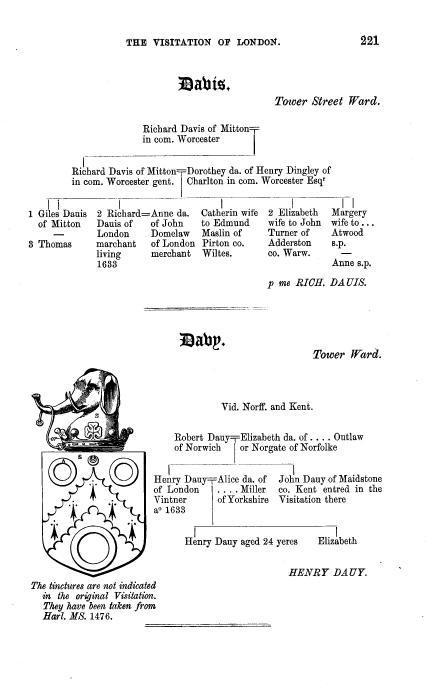

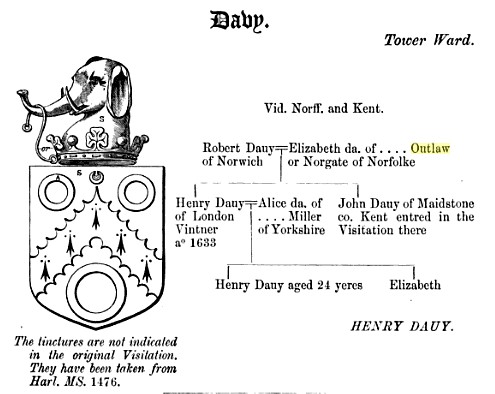

The visitation of London, anno domine 1633, 1634, and 1635 Volume II … Harleian Society v.17

The Visitation of London, 1633, 1634 and 1635 - Online

Tower Ward - Robert Dauy Davy of Norwich = Elizabeth Da. of ... Outlaw of Norgate of Norfolke

Robert Davy b. of, Norwich, Norfolk, England d. Y

Henry Davy b. 19 Sep 1577 of, Tower Ward, Allhallows, Barking, London, Middlesex, England d. 1640

---- >>> Back to Outlawe Research Journal - Page 3 Go to Page 5